Even those who agreed that jobs will come back in “the long run” were concerned that “displaced wage-earners must eat and care for their families ‘in the short run.’”

This analysis reconciled the reality all around—millions without jobs—with the promise of progress and the benefits of innovation. Compton, a physicist, was the first chair of a scientific advisory board formed by Franklin D. Roosevelt, and he began his 1938 essay with a quote from the board’s 1935 report to the president: “That our national health, prosperity and pleasure largely depend upon science for their maintenance and their future improvement, no informed person would deny.”

Compton’s assertion that technical progress had produced a net gain in employment wasn’t without controversy. According to a New York Times article written in 1940 by Louis Stark, a leading labor journalist, Compton “clashed” with Roosevelt after the president told Congress, “We have not yet found a way to employ the surplus of our labor which the efficiency of our industrial processes has created.”

As Stark explained, the issue was whether “technological progress, by increasing the efficiency of our industrial processes, take[s] jobs away faster than it creates them.” Stark reported recently gathered data on the strong productivity gains from new machines and production processes in various sectors, including the cigar, rubber, and textile industries. In theory, as Compton argued, that meant more goods at a lower price, and—again in theory—more demand for these cheaper products, leading to more jobs. But as Stark explained, the worry was: How quickly would the increased productivity lead to those lower prices and greater demand?

As Stark put it, even those who agreed that jobs will come back in “the long run” were concerned that “displaced wage-earners must eat and care for their families ‘in the short run.’”

World War II soon meant there was no shortage of employment opportunities. But the job worries continued. In fact, while it has waxed and waned over the decades depending on the health of the economy, anxiety over technological unemployment has never gone away.

Automation and AI

Lessons for our current AI era can be drawn not just from the 1930s but also from the early 1960s. Unemployment was high. Some leading thinkers of the time claimed that automation and rapid productivity growth would outpace the demand for labor. In 1962, MIT Technology Review sought to debunk the panic with an essay by Robert Solow, an MIT economist who received the 1987 Nobel Prize for explaining the role of technology in economic growth and who died late last year at the age of 99.

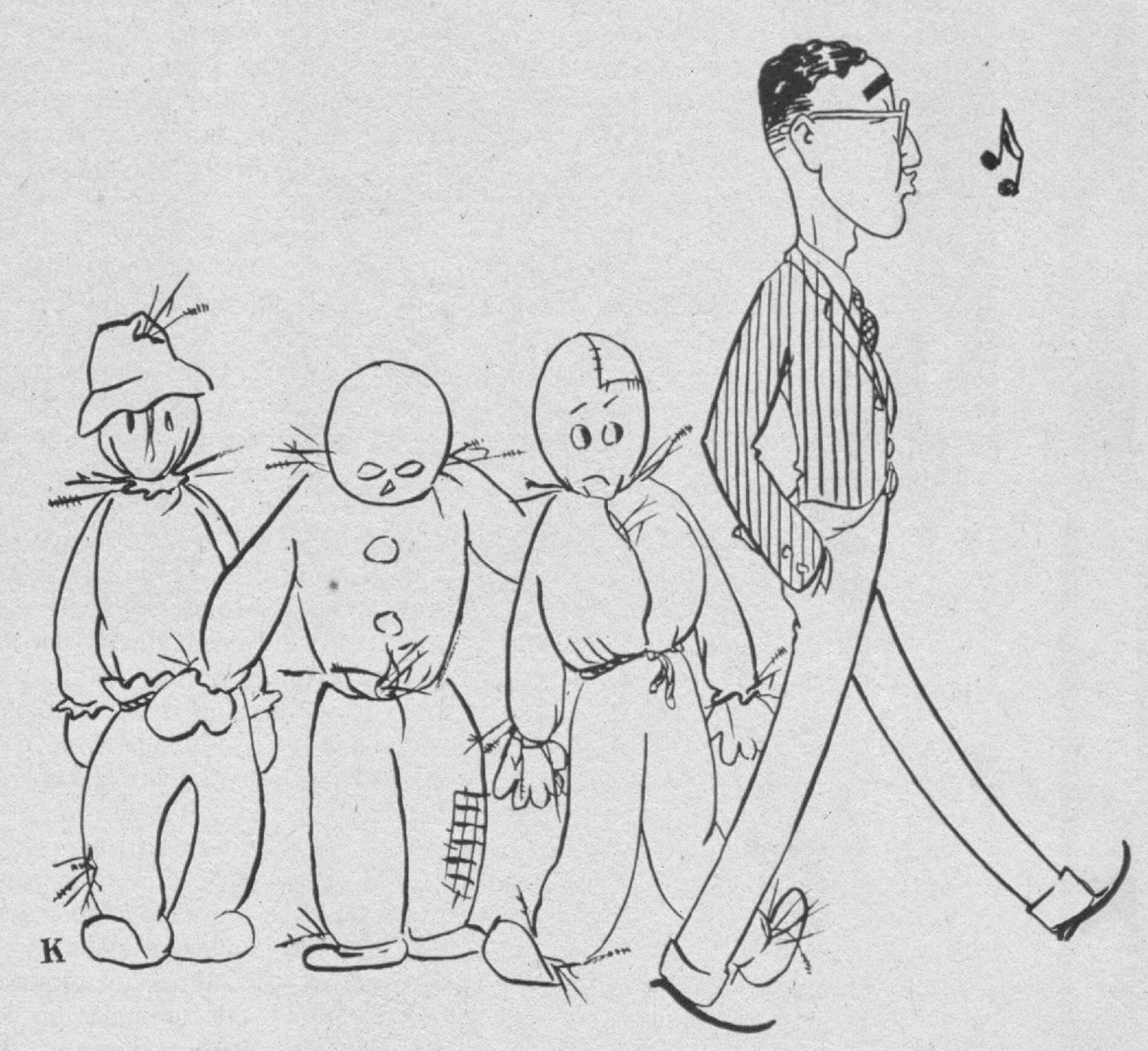

Robert Solow’s 1962 essay was illustrated by a cartoon of a Solow-looking character whistling past a trio of straw men (presumably jobless ones).

Robert Solow’s 1962 essay was illustrated by a cartoon of a Solow-looking character whistling past a trio of straw men (presumably jobless ones).

In his piece, titled “Problems That Don’t Worry Me,” Solow scoffed at the idea that automation was leading to mass unemployment. Productivity growth between 1947 and 1960, he noted, had been around 3% a year. “That’s nothing to be sneezed at, but neither does it amount to a revolution,” he wrote. No great productivity boom meant there was no evidence of a second Industrial Revolution that “threatens catastrophic unemployment.” But, like Compton, Solow also acknowledged a different type of problem with the rapid technological changes: “certain specific kinds of labor … may become obsolete and command a suddenly lower price in the market … and the human cost can be very great.”

These days, the panic is over artificial intelligence and other advanced digital technologies. Like the 1930s and the early 1960s, the early 2010s were a time of high unemployment, in this case because the economy was struggling to recover from the 2007–’09 financial crisis. It was also a time of impressive new technologies. Smartphones were suddenly everywhere. Social media was taking off. There were glimpses of driverless cars and breakthroughs in AI. Could those advances be related to the lackluster demand for labor? Could they portend a jobless future?