Many people question whether the current artificial intelligence boom will end in the same way that the dotcom bubble burst.

It’s understandable, as there are many similarities, especially with the exuberance seen this past week in the stock market following Nvidia Corp.’s earnings print. Although it’s easy to dismiss AI as a completely different era, there are some stark similarities that are worth remembering.

Like all waves, there are also major differences. Two of the most evident are the speed of innovation and the quality of today’s companies leading the AI charge. Like the internet, AI will be ubiquitous and available for virtually all organizations to leverage, not just traditional tech firms. As well, many patterns of the dotcom era are repeating and worth examining in more detail.

In this Breaking Analysis, we look back at the events leading up to the dotcom and AI booms and analyze the similarities and differences between these two transformative eras.

Irrational exuberance

This phrase was made famous by Alan Greenspan, the Fed chairman during the internet bubble. Let’s look at the events leading up to the dotcom bubble, what the conditions were that fueled it and what happened in the aftermath.

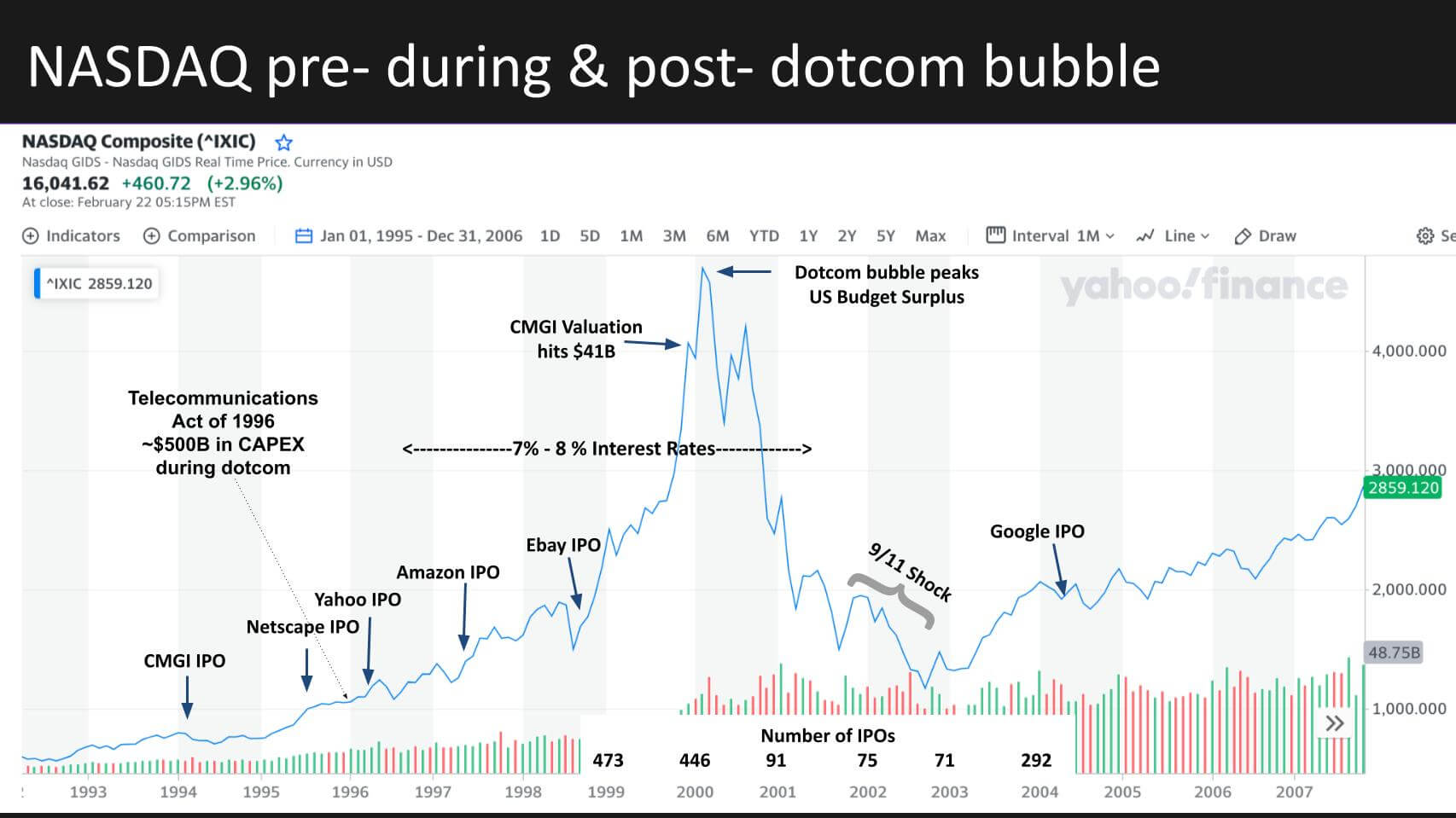

By the mid-1990s, it was clear that the most prominent monopoly in tech, IBM Corp., had relinquished its crown. Wintel, the powerful virtual combination of Microsoft Corp. and Intel Corp., were the defining platforms of the pre-dotcom era. On this chart we show merely a fraction of the relevant milestones and conditions that fueled the dotcom bubble.

We start in 1994 with a company not well-known today called CMGI going public. It was a nothing shell that ended up becoming a prominent dotcom investment firm and the poster child for pump-and-dump, unsustainable businesses. But what really got the dotcom boom started was the Netscape Communications Corp. initial public offering of stock less than a year after its first browser launched.

A spate of IPOs ensued including a few we’re showing such as Yahoo Inc., Amazon.com Inc. and eBay Inc. Note the number of IPOs – we show the data starting in 1999 at the bottom of the chart. There were 473 companies that went public in ’99, 446 the following year and a steep reduction after the bubble burst with 91 in 2001, bottoming at 71 in 2003, far fewer than even 2022, which was a terrible year for IPOs.

Massive CAPEX created opportunities for huge wealth creation

But let’s back up to 1996. The Telecommunications Act, signed by President Clinton, opened up competition in communications and also the floodgates for investment. Companies such as Global Crossing, WorldCom, Enron, Qwest, Lucent, Level 3 skyrocketed and public telcos poured nearly $500 billion into building out the internet between 1996 and 2001.

Much of that funding came from debt these companies took on, which became an anchor after the bubble burst. That capital investment was substantial and approached $1 trillion in today’s dollars.

Similar to today’s AI rush, you had all this investment and enthusiasm to the point where CMGI hit a valuation of $41 billion. The company’s CEO was dubbed the Warren Buffett of dotcom investing. As it turns out, CMGI owned a bunch of distressed assets, and after the bubble burst, it lost 99% of its value. CMGI is one of dozens if not hundreds of stories of wealth creation that created billionaires and multimillionaires and left many out in the cold when the music stopped.

Y2K was another tailwind for tech

Leading up to the end of the millennium, information technology shops had a blank check to fix the Y2K bug. Many applications used only two digits to represent the year. It meant that with ’00, 2000 would be indistinguishable from 1900 and so forth. The fear was when the clock struck midnight on 12/31/99, the world’s software would go into an unpredictable glitch, financial systems would come to a grinding halt, and the world’s economy would cease to function.

The industry spent hundreds of millions of dollars to fix the problem and when the year 2000 came, the world didn’t end. Many in the IT community and U.S. government credited the fine work of the technology industry to avert a crisis. But critics pointed out that many countries and regions didn’t implement a fix and their worlds didn’t end, creating a backlash and narrative that Y2K was nothing more than a tech boondoggle.

This perception would linger and come back to haunt many chief information officers after the bubble burst.

There’s always a top. Dotcom was no different

The bubble peaked in March of 2000 and it did so during a time when interest rates were holding between 7% and 8%. At the peak, the U.S. government had a budget surplus that in part fueled the boom. Clinton’s tax hikes were used to chip away at U.S. debt and balance the budget. Wall Street loved it and poured money into internet stocks.

The bubble really didn’t pop until the world realized that much of the venture funding was going to internet companies with no viable business model. These distressed assets were using venture capital to buy networking equipment from Cisco Systems Inc., servers from Sun Microsystems Inc., storage from EMC Corp., Oracle Corp. database licenses, Dell PCs and so forth, fueling a tech boom along side the rise of internet stocks.

These startup companies were also advertising like crazy on VC-backed internet portals such as Yahoo and Lycos. It was a self-fulfilling, circular reference that came crashing down once the VC money dried up.

9/11 prolongs the pain. IT doesn’t matter

Just when folks thought the falling knife would hit bottom and markets would return to abnormal exuberance, 9/11 happened and the tech industry went into a long funk. Silicon Valley was a ghost town for years with empty offices. The sentiment on enterprise tech was so bad and punctuated by a famous article in the Harvard Business Review, IT Doesn’t Matter, by Nicholas Carr. In it, Carr argued that IT was no longer a strategic resource and could not deliver sustainable competitive advantage. IT called a “code red” and every CIO on the planet had to scramble to justify their existence.

It wasn’t until the Google IPO the following year that tech markets slowly began to come back and people realized that a new era was upon us, that IT still mattered but it was going to transform led by consumer companies such as Google, which published its critical work on the Google File System, spawning new thinking around how to do IT at global scale.

Amazon Web Services launched in 2006, but the country was deep into two wars and a financial crisis ensued shortly thereafter that lasted from late 2007 and well into 2009. Lots of innovation was occurring with social, cloud, big data and mobile (with the iPhone launch), but the momentum in enterprise tech was put on life support because of the financial crisis, which ushered in a long period of super-cheap money and fueled the next wave.

Fundamental laws of tech innovation

Before we go to the comparisons and differences with the AI era, it’s worth looking at the prevailing laws of the dominant eras.

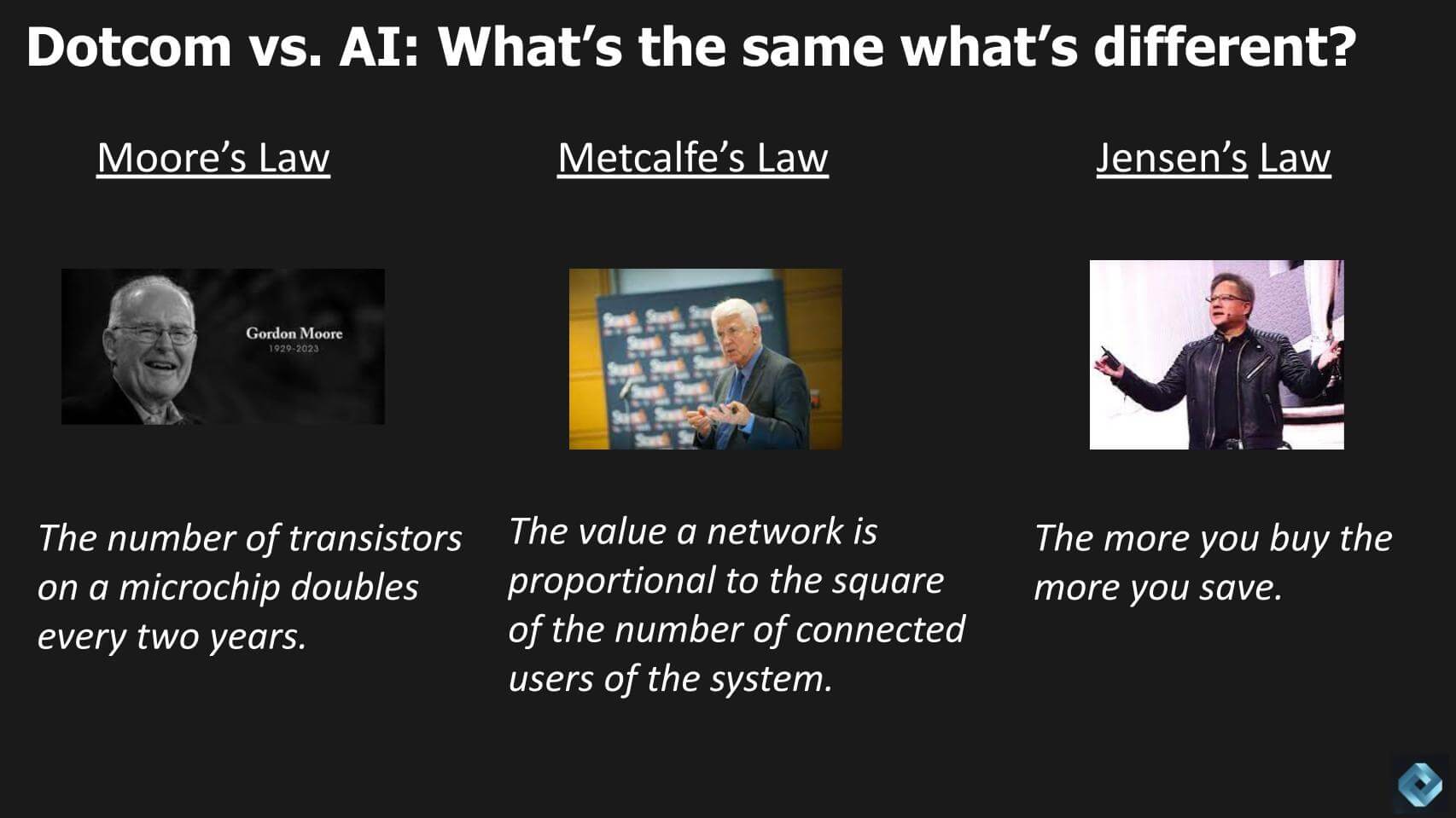

Leading up to the dotcom and well into it, Moore’s Law was in full swing. Named after Gordon Moore, it was the mantra of doubling the number of transistors on a chip every 24 months.

The dotcom era was fueled by a paradigm shift in value creation, best described by Metcalfe’s Law, which talks to network effects. Bob Metcalfe, co-inventor of Ethernet, posited that the value of a network increases exponentially even as the connected users increases linearly. Thought of another way, when there are two people with phones on the network there’s not much value but when there are billions, the value curve bends exponentially. Metcalfe’s Law didn’t replace Moore’s Law; rather, it was additive.

Now we’re entering the AI era. Nvidia Chief Executive Jensen Huang claims that the more graphics processing units you buy, the more you save. We’re calling this “Jensen’s Law.” And he might be right. His premise is that compared with general-purpose CPUs, his superchips can run AI workloads 12 times faster and are 20 times more energy-efficient. His argument is a direct shot at Moore’s Law because at a doubling of performance every two years, it would take the better part of a decade to achieve these results.

Whether Moore’s Law is dead or not is an active debate that we’ve addressed in this series previously. Huang and many others often remind us of its death while Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger vehemently defends its premise as alive and well. But clearly new approaches to silicon design are hitting the market and are needed in the AI era.

The AI cycle is accelerated (pun intended)

Let’s take a closer look at the period leading up to the AI boom and where we are today.

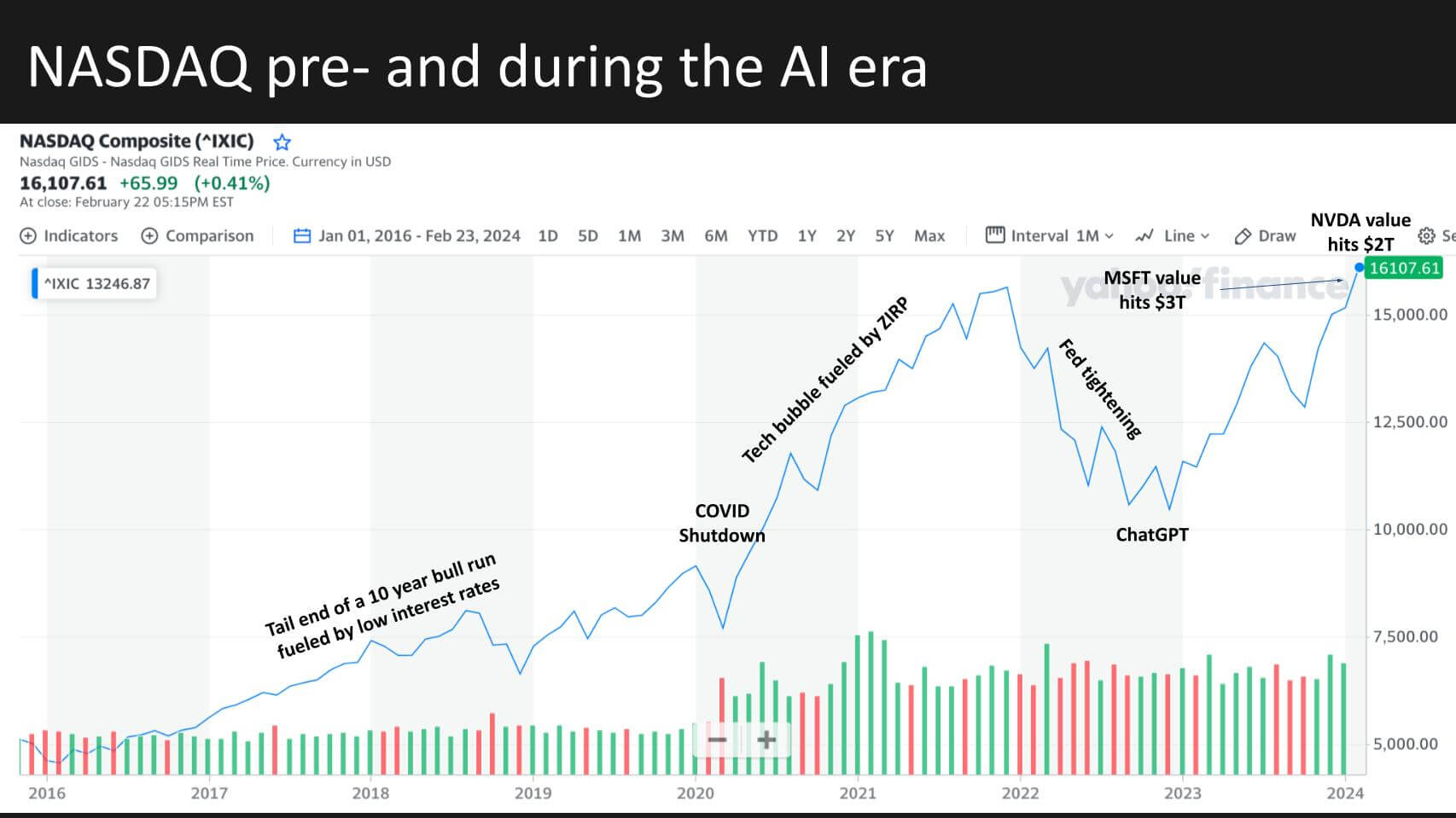

The AI era was preceded by the end of a 10-year bull run fueled by near-zero interest rates. It was an epic time period powered by the cloud and software as a service, which AWS kicked off before the financial crisis.

In fact, during the financial meltdown of 2008 and 2009, many chief financial officers of companies that were reluctant to try the cloud started to migrate as a way to reduce IT CAPEX and associated heavy lifting. Once they tried cloud, it became evident it was a better operating model and we saw a decade of tremendous growth fueled by cloud.

That tech boom was interrupted for a very short time when COVID hit but then took off as organizations had no choice but to migrate to the cloud. The end of zero-interest rate policy halted the run and tech spending began decelerating during 2022. But OpenAI’s ChatGPT was announced late in the year, coinciding with a pause to Fed hikes and the modern AI run began.

The trillionaires’ club grows

Last year, Microsoft added $1 trillion to its valuation, most of that from AI frothiness, and stands at $3 trillion today. Early on Friday morning, Feb. 23, Nvidia’s market value hit $2 trillion.

The catalyst for all this momentum was the announcement of ChatGPT and the realization that generative AI was going to impact every company, every industry and most people on the planet — similar to the internet.

ChatGPT was a Netscape-like moment

It feels like ChatGPT is a bigger thing than the Netscape browser, but at the time, the ability to surf the World Wide Web was pretty remarkable. Looking back, that experience was novel albeit subpar relative to today’s ability to stream video and navigate rich websites. The quality of that browsing experience improved by orders of magnitude and the large language model-powered experience is likely to see similar patterns.

Regardless, these were the kickstarter moments for both eras and, like Netscape, OpenAI is top of mind.

The chart above should give you an idea of just how much mindshare OpenAI has today. This graphic from ETR’s emerging technology survey (ETS), shows Net Sentiment on the vertical axis, which represents intent to engage, and Mind Share from a survey of more than 1,500 IT decision makers.

Like Netscape, OpenAI has much greater momentum and mindshare than its competitors — so much so that we had to put a red box around OpenAI’s position on this graph because it’s literally off the charts. The pack of AI companies however has raised close to $10 billion, while Netscape’s competition came from a few no name startups, some open-source browsers such as Firefox and of course Microsoft.

Many of the gen AI players on this chart may not become household names and go the way of those early browser competitors. Open-source LLM alternatives are emerging, similar to what happened with the browser. The most prominent and well-known open source platform is Meta Platforms Inc.’s Llama, but there are dozens in the mix. As well, just as Google search disrupted the internet portals, we’re seeing chat-style engines such as Perplexity vying for mindshare and adoption. So some disruptions similar to dotcom will potentially evolve.

Like the internet buildout, massive CAPEX is fueling the AI boom

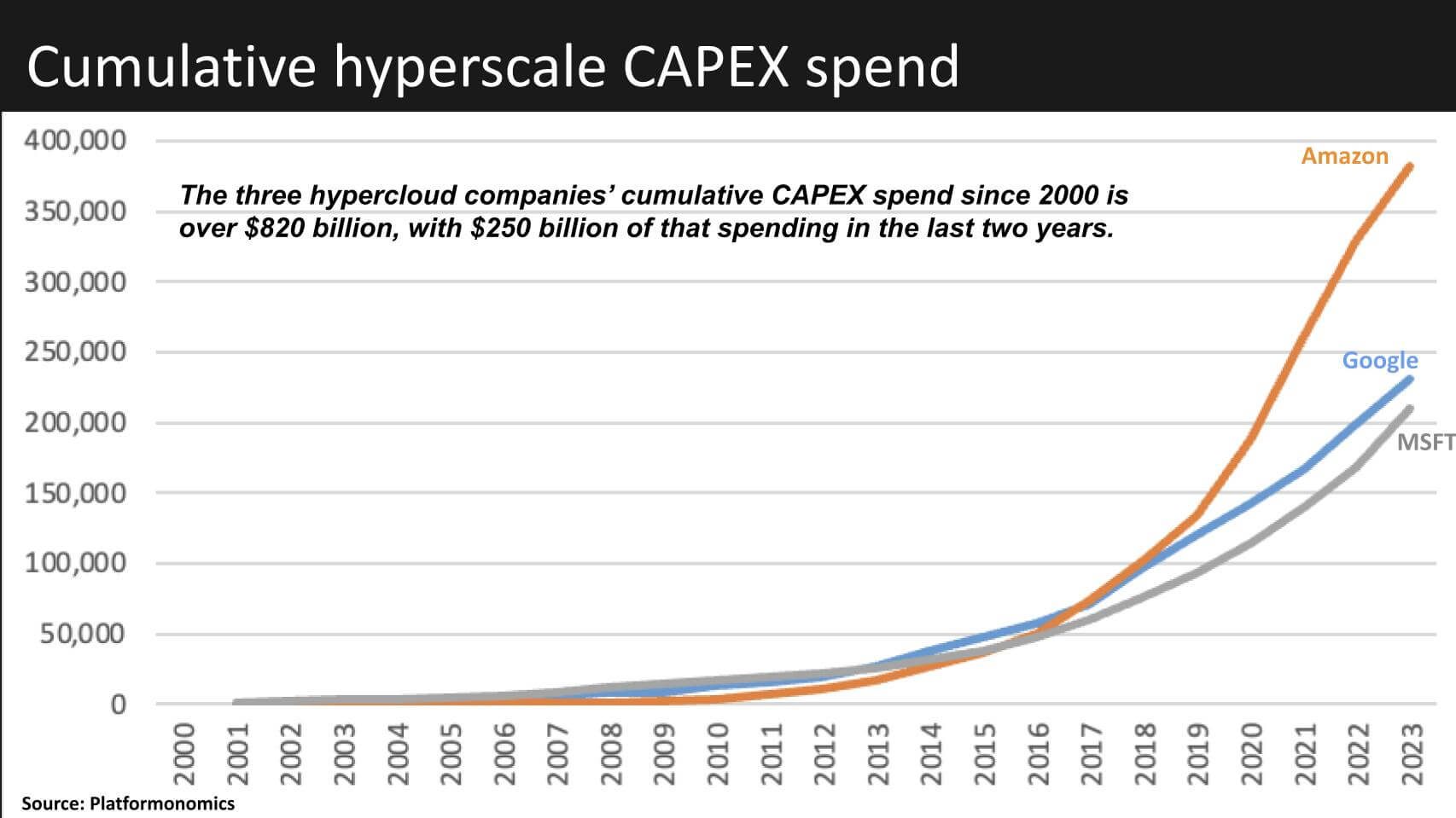

One other major similarity between dotcom and the AI era is capital investment.

This chart from Charles Fitzgerald shows how much investment the hyperscalers are pouring into CAPEX to support cloud and now AI. Amazon’s CAPEX includes more than AWS because of the company’s warehouse infrastructure. But we’re seeing a buildout at quite a similar scale as saw with telcos and internet service providers during the dotcom boom.

As “Fitzy” points out in his last post, Nvidia’s data center revenue was approximately equal to 50% of the hyperscalers’ CAPEX last quarter. By inference from Nvidia’s statements, cloud companies spent nearly $10 billion on GPUs last quarter, fueling the AI boom. By comparison, Nvidia’s CAPEX is tiny compared with the hyperscalers because Nvidia doesn’t make its chips, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. does.

So the similarities are ther,e but the funding sources are much different. The AI CAPEX funding comes from hyperscale giants that are flush with cash versus the dotcom communications providers that were drowning in debt. For example, adding Apple Inc. to the mix, since it will eventually get into the game in a big way, combined, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft and Meta have nearly $380 billion in cash on their balance sheets. Only a portion of their CAPEX investments hit the income statement as depreciation costs over N years, so they’re loading up their AI war chests with infrastructure, betting the AI era will pay big dividends.

Many similarities and differences between dotcom and AI

In summary, let’s examine the parallels and differences between the dotcom era and the current surge in artificial intelligence, highlighting key players, market dynamics and technological advancements. Netscape and OpenAI have been highlighted as pivotal innovators in their respective times. Microsoft plays a significant role in both eras. In the dotcom era, it killed Netscape by bundling Internet Explorer into Windows. Today it is integrating OpenAI into its software estate and ecosystem.

CAPEX is fundamental

The Web was funded by telco CAPEX as hyperscalers are funding the AI buildout. But there was no internet or cloud at the time, so this time the pace is accelerated.

Picks and shovels are highly valued at the start

The core infrastructure – so-called “picks and shovels” companies — were highly valued in the dotcom era (for example, Cisco, Sun, EMC, Oracle). Similarly, Nvidia, AWS, Microsoft and Google are seen as critical players. Meta is a wildcard with its open-source Llama models. Open standards won the day for the Web and likely will play a major role in the AI era.

That said, Nvidia and the hyperscalers have more durable business models. As well, the injection of AI into SaaS will accelerate adoption. There were no SaaS companies in the days of the early Web. Cloud enabled SaaS to thrive and SaaS players will inject AI into their platforms. While new AI native apps will emerge, the established SaaS players will accelerate innovation.

Closed versus open

AOL was the granddaddy of the internet and a closed proprietary walled garden like NVIDIA & the hyperscalers are today. But the open Web won the day in the Internet era and open source software like Meta’s Llama and others looms large.

The difference is that AOL had a weak value prop and was ripe for disruption. Perhaps if it opened up, it could have evolved. But Nvidia and the hyperscalers have massive moats – much stronger than the fragile dotcom companies we talked about earlier. Open source will nonetheless play a role, in our view.

Investor FOMO

The markets back then were irrational, with lots of investor fear of missing out. Anything with a dotcom address went up to the moon. We’re seeing some of that irrational exuberance again. But seven companies have really led the AI boom. And the supporting cast of SaaS companies are much more durable than the frauds of the dotcom. Snowflake Inc., Adobe Inc., Workday Inc., Salesforce Inc., ServiceNow Inc., Oracle, SAP SE and many more will power this AI era.

The stock market was “bubblicious” as it is today, but companies then had no earnings. A major difference is IPOs were booming back then, as we showed. It’s not the case today. Moreover, today’s leaders are highly profitable. Many comparisons are being made between Nvidia and Cisco, which during the dotcom boom was the most valuable company in the world.

But Cisco never had monopoly potential. Nvidia does. Whether it can maintain its lead remains to be seen, but in our view it has a many-years lead and if it executes, it could dominate for a decade or more, riding Jensen’s Law.

New, hot markets follow similar patterns

Embryonic markets have similar patterns. Version 1.0 leads to 2.0 and the solutions keep getting better and better. Continuous innovation occurs if free cash flow can be generated, creating a flywheel effect. We’re seeing similar patterns today that we saw in dotcom, but the difference with AI is the pace of innovation is much faster because of the ubiquity of the internet and cloud. AI has those platforms to leverage, whereas dotcom didn’t.

Novel user experiences define an era

Like in the dotcom days, we’re witnessing a completely new set of user experiences. The difference this time around is we’re talking about the replacement of cognitive functions for the first time ever.

Conclusion

Similar to the dotcom era, with AI, we’re looking at a virtually unlimited and incalculable total available market. At the same time, born out of the dotcom boom, we saw the rise of social media, which brought unknown risks. Who knows what artificial general intelligence will bring out of the AI era?

The trajectory of AI mirrors the dotcom era in several respects, characterized by rapid innovation, significant market potential and investor enthusiasm. However, the landscape today is marked by more durable business models, a faster pace of innovation, and a shift toward replacing cognitive functions. While the future holds great promise, it also necessitates attention to emerging risks and investors getting out over their skis.

As well, a major difference is regulatory oversight. Globally, tech is getting much more scrutiny much earlier in the cycle. Although public policy played a big role in the buildout of internet infrastructure, its role early in the cycle with respect to software regulation is new.

The question on everyone’s mind is whether the market is overdone and will it blow up at some point? The answer is yes, probably. When is anyone’s guess. But unlike the dotcom bubble, it won’t likely be because the cloud companies are running out of money and can’t buy GPUs any more. They may stop buying, but the bubble burst will be different. Today’s AI firms are much more durable than the dotcom companies.

Rather, the disruption is more likely to come from external factors. Some examples:

- China invades Taiwan and chokes semiconductor supply

- War and acts of terror

- Climate disaster

- Financial crisis

- Some other external event that shakes the economy.

Hopefully that event will not decimate humanity and we’ll recover to see the wonderful promises of AI come to fruition.

What do you think? Are the similarities to dotcom greater than the differences, or is it full speed ahead and damn the torpedoes?

Keep in touch

Thanks to Alex Myerson and Ken Shifman on production, podcasts and media workflows for Breaking Analysis. Special thanks to Kristen Martin and Cheryl Knight, who help us keep our community informed and get the word out, and to Rob Hof, our editor in chief at SiliconANGLE.

Remember we publish each week on theCUBE Research and SiliconANGLE. These episodes are all available as podcasts wherever you listen.

Email david.vellante@siliconangle.com, DM @dvellante on Twitter and comment on our LinkedIn posts.

Also, check out this ETR Tutorial we created, which explains the spending methodology in more detail. Note: ETR is a separate company from theCUBE Research and SiliconANGLE. If you would like to cite or republish any of the company’s data, or inquire about its services, please contact ETR at legal@etr.ai or research@siliconangle.com.

Here’s the full video analysis:

All statements made regarding companies or securities are strictly beliefs, points of view and opinions held by SiliconANGLE Media, Enterprise Technology Research, other guests on theCUBE and guest writers. Such statements are not recommendations by these individuals to buy, sell or hold any security. The content presented does not constitute investment advice and should not be used as the basis for any investment decision. You and only you are responsible for your investment decisions.

Disclosure: Many of the companies cited in Breaking Analysis are sponsors of theCUBE and/or clients of theCUBE Research. None of these firms or other companies have any editorial control over or advanced viewing of what’s published in Breaking Analysis.

Image: DALL-E

Your vote of support is important to us and it helps us keep the content FREE.

One click below supports our mission to provide free, deep, and relevant content.

Join our community on YouTube

Join the community that includes more than 15,000 #CubeAlumni experts, including Amazon.com CEO Andy Jassy, Dell Technologies founder and CEO Michael Dell, Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger, and many more luminaries and experts.

“TheCUBE is an important partner to the industry. You guys really are a part of our events and we really appreciate you coming and I know people appreciate the content you create as well” – Andy Jassy

THANK YOU