On Feb. 3, Tom

Snyder, Executive Director of RIoT, hosted the annual State of the Region

Address at Raleigh Founded. Embracing the State of the Union theme, Tom

discussed the economy and jobs, domestic and foreign affairs and North

Carolina’s opportunities and threats. You can read a written version of that

address here.

Economic security and current events

I’d like to start

this year’s State of the Region from a place that may feel uncomfortable, but

necessary.

Last month,

Minneapolis became the center of a national conversation about institutional

trust, individual safety, and public confidence in economic and civic systems.

The killing of Renee Good and Alex Pretti, on the heels of at least six other ICE-related deaths in Texas, Illinois and California sparked widespread

demonstrations, sit-ins, and civil unrest that resonated far beyond the Twin

Cities.

These deaths, and

the reactions they provoked, are not merely local news. They cut to a deeper,

broader question about how people feel about their future, whether they

feel secure in their communities, in their institutions, and in the basic

economic and social contracts that undergird a functioning society.

This speech isn’t

a commentary on immigration policy. Instead, I want to acknowledge the context

in which we gather: a time when the absence of economic comfort, when people

feel unstable, overlooked, or without clear opportunity, can fuel broader

social tension.

Because the truth

is this: when people feel economically insecure, anxiety rises. When people

feel that hard work does not lead to opportunity, faith in systems erodes. When

people feel disconnected from the economic engines around them, they turn

inward or outward with equal intensity.

Economic comfort

is one of the strongest stabilizing forces any region can have. And that is

what makes the work that RIoT conducts so important. It is what drives our

passion to support entrepreneurship, helping people to build income and

generational wealth through small business creation and sustainment.

And that leads us directly back to the core question

of this address: What is the State of our Region in 2026, and what must we do

to build an economy that produces broad economic comfort, not just

headline growth?

The economic baseline

By conventional standards, North Carolina’s economy remains strong. As

of late 2025, the state’s labor force exceeded 5.29 million people, with total

nonfarm employment at approximately 5.12 million jobs. Unemployment has

remained consistently below the national average, hovering around 3.7 percent,

signaling a tight labor market rather than one in distress. Year-over-year job

growth of roughly 1.5 to 2 percent places North Carolina squarely in the middle

of the national pack. We are not overheating, but not stagnating.

Wages continue to rise. Average private-sector hourly wages reached

roughly $33 per hour, increasing more than 4 percent year over year, with

higher averages in metro areas like Charlotte and the Triangle. At the same

time, housing, transportation, and childcare costs continue to pressure

household budgets, particularly for younger families and middle-income workers.

Population growth reinforces this picture. North Carolina surpassed 11

million residents, adding more than 80,000 net domestic migrants in a single

year. People are still choosing to move here, a sign of confidence in the

state’s economic prospects and quality of life.

Taken together, these numbers describe an economy that is growing. But

they do not yet tell us how resilient that growth will be as technology

accelerates.

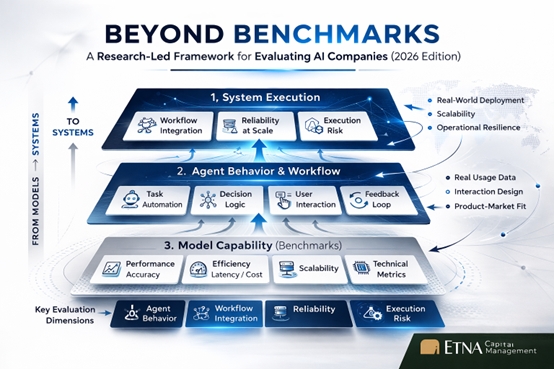

Work in transition: AI, automation, and uneven

exposure

Beneath the topline indicators, the structure of work is changing

rapidly. As you already know, AI is a primary lever of this current

change. To give an idea of how pervasive

AI has become, consider that today the major internet monitoring companies like

Cloudflare and Akamai report that only 20-25% of all internet traffic is

conducted by humans. Everything else is a combination of bots, crawlers, RAG

engines and other machine-driven effort.

Large language models are part of the shift. Each human query to a

large language model typically drives 5-15 web queries to “trusted authority”

sites, which were previously vetted by millions of digital interactions.

Agentic AI will drive even more non-human web traffic.

AI has not eliminated work wholesale, but it has compressed job

descriptions, automated tasks once considered secure, and raised expectations

for output per worker. In logistics, manufacturing, administrative services,

and food processing, all major employment sectors in North Carolina, between 30

and 45 percent of current tasks are already technically automatable with

existing or near-term technology. Robotics adoption in warehousing and

manufacturing is growing at double-digit annual rates, driven less by novelty

than by labor scarcity and cost pressure.

This does not point to mass unemployment. It points to volatility.

Humans that augment their workflows with AI become far more productive,

particularly for mid and senior career positions that replace with AI, work

traditionally conducted by entry level workers. Productivity gains driven by

automation and artificial intelligence are reshaping work faster than

institutions are adapting.

Workers who can adapt and reposition themselves will often do well.

Workers whose roles are automated faster than they can transition will

experience periods of insecurity. The challenge for regions is not stopping

technological change, but ensuring that opportunity keeps pace with disruption.

The human jobs of now and the future

Let’s

get more specific about what adapting and repositioning actually means.

If

we accept that AI will become exceptionally good at technical execution, and in

fact is an expert at pattern recognition, optimization, and repeatable

decision-making, then the obvious question is: where do humans still create

durable value?

The

answer is not in competing with machines at what they do best. It is in doing

the things machines are structurally bad at: identifying unmet needs,

navigating ambiguity, building trust, persuading customers, and stitching

together solutions across messy real-world constraints.

There

has never been a single way to make a living. There are millions of niche

markets, and new ones emerge every year. To give an example, in New York City,

people rent unused air rights above buildings to developers to work around

zoning limits. Highly creative and not the kind of niche market opportunity

likely to be identified by or executed upon by an AI.

In

North Carolina, entrepreneurs build profitable businesses around hyper-local

logistics, specialized manufacturing services, regulatory navigation,

agricultural optimization, and industry-specific software that is far too

narrow to interest large incumbents.

In

nearly all of these markets, the critical work is still human. AI may help

design a product, automate a back office, or optimize pricing. It might even

operate the equipment. But people still identify the opportunity, initiate the

relationship, explain the value, negotiate the deal, and ensure the customer

succeeds. Selling, trust-building, and accountability remain human activities.

Entrepreneurship is not threatened by AI. It is amplified by it.

Entrepreneurs

equipped with AI can reach markets faster and at lower cost. They prototype

sooner. They operate with smaller teams. They replace overhead with software

and redirect effort toward customer acquisition and problem-solving. What

disappears are not entrepreneurs, but generic roles that once existed between

idea and execution.

The

human jobs of the future are not narrowly technical. They are combinatorial.

They sit at the intersection of domain knowledge, customer empathy, persuasion,

and execution. Regions that understand this will focus less on training people

for static job titles and more on equipping them to create work where none

previously existed.

So

how is North Carolina positioned to capture this future, and how is our region

supporting entrepreneurs? Let’s look

first at our regional advantages.

Industry diversity: A structural advantage in a

horizontal technology era

This is where North Carolina’s long-standing diversity of industries

becomes more than a hedge. No single sector accounts for more than one-fifth of

the state’s GDP. Finance, healthcare, life sciences, manufacturing, logistics,

agriculture, energy, and technology all play material roles in the economy.

Historically, that balance protected the state from sector-specific downturns.

In an AI-driven economy, it becomes a competitive advantage.

AI is not a vertical industry. It is a horizontal capability whose

value is unlocked only when embedded into real businesses solving real

problems. Regions that are over-rotated toward a single sector eventually hit

diminishing returns. Regions with breadth can apply AI across multiple domains

simultaneously, shortening feedback loops and accelerating adoption.

In North Carolina, startups and innovators can pilot solutions in

hospitals, factories, farms, logistics hubs, and research labs without leaving

the state. That proximity reduces commercialization risk and increases the

likelihood that productivity gains spread broadly rather than concentrating

narrowly.

Agriculture as a case study in applied innovation

Agriculture illustrates this dynamic clearly. When measured

comprehensively, agriculture contributes more than $90 billion annually to

North Carolina’s economy through direct and indirect activity. Yet employment

in the sector continues to decline, reflecting labor shortages, consolidation,

and rising productivity demands.

Technology adoption is no longer optional. Precision sensing,

automation, robotics, and data-driven decision systems are becoming

prerequisites for competitiveness. What has changed is accessibility.

Initiatives like The Source in Wilson represent a new model of economic

development, allowing small and mid-sized farmers to experiment with advanced

technology before committing scarce capital. By lowering the cost of adoption

and accelerating learning, these testbeds help keep ownership local, improve

resilience, and strengthen rural economies.

This is entrepreneurship in practice, even when it does not carry that

label.

Research strength is not the problem — Translation is

North Carolina’s research capacity remains one of its defining

strengths. The state consistently ranks among the top ten nationally in total

R&D expenditures, with annual spending exceeding $9 billion. The Triangle’s

three major research universities alone attract more than $2.5 billion per year

in research funding, placing the region among the most research-dense in the

country on a per-capita basis.

Discovery is not the bottleneck. Translation is. Historically, programs

like SBIR and STTR served as the bridge between research and commercialization,

providing early validation and non-dilutive capital to first-time founders and

deep-technology startups. Over the past decade, North Carolina firms received

roughly $170–220 million annually through these programs, consistently placing

the state in the national top tier.

Today, uncertainty around federal reauthorization and appropriations

has weakened that bridge. There is hope. A recent analysis in the Economist

showed that over the past 40 years, Republican led Congresses have provided

higher research funding to every single federal agency (except the Department

of Energy) than Democratic led Congresses. But as of today, SBIR and STTR

funding has still not been reauthorized in the US budget.

BREAKING NEWS – As I was about to hit “publish” on

this article, the House passed a budget to reopen the US government and it is

headed to Trump’s desk for signature. While this budget still does not include

SBIR/STTR reauthorization, it does include $1B for the Small Business

Administration, including $330M for Entrepreneurial Development Programs and

$160M for Small Business Loans.

Even short disruptions in award cycles can delay company formation,

stall hiring, and push intellectual property to be licensed or relocated

elsewhere. So where do entrepreneurs launching tech research-based startups

turn instead?

NC Innovation: A competitive differentiator among

states

In this environment, translation capacity becomes strategic. NC

Innovation represents one of the most ambitious state-backed commercialization

efforts in the country. Funded through a $500 million taxpayer-supported

endowment, NC Innovation is designed to move university research toward market

readiness before a company even exists. It allows for focus on proof-of-concept

work, prototyping, and commercialization planning across all UNC System

institutions.

Few states have built a comparable mechanism at this scale. Some, like

Utah, operate innovation intermediaries, but typically at an order of magnitude

smaller annual funding. Many others rely primarily on time-limited federal

programs such as SSBCI, which are broader in scope but not purpose-built for

university research translation.

Nationally, fewer than five percent of university disclosures ever

result in a startup. Regions that improve early translation measurably improve

those odds. NC Innovation functions as a stabilizer in the capital stack,

reducing dependence on any single federal program and increasing the likelihood

that intellectual property becomes companies and jobs in North Carolina.

This is an area where the state is quietly leading.

Entrepreneurship and capital: A comparative weakness

While North Carolina is strong in research translation, it is

comparatively weaker in one important area: direct financial support for

startups.

Several neighboring states have moved aggressively to deploy

taxpayer-funded equity capital into early-stage companies. Tennessee, for

example, has committed more than $100 million through its Fund Tennessee

initiative, including a dedicated venture equity component that invests

directly in startups and venture funds. Virginia appropriates roughly $17M in

taxpayer dollars annually to support startup grants, fund accelerator programs

and take equity investments in the most promising Virginia companies. The South

Carolina Research Authority, a public entity, just announced a new program that

will provide $5M to entrepreneurial support organizations across the state.

North Carolina does not currently operate a comparable statewide,

taxpayer-funded equity program. This gap is not theoretical. Entrepreneurs

notice it. Investors notice it. And over time, it affects where companies

choose to form, raise capital, and scale.

While North Carolina excels at helping research move closer to

commercialization, it lacks a complementary mechanism to provide early risk

capital once companies are formed. Addressing this imbalance is not about

copying other states. It is about ensuring that the state’s innovation pipeline

does not narrow precisely at the point where companies need capital most.

Silver lining: Early stage private capital

While

North Carolina lacks a large, taxpayer-funded venture equity program, it

benefits from a quieter but meaningful strength: a growing concentration of

early-stage private capital, particularly in the Triangle.

In

fact, right here in this building, Scot Wingo leads the Triangle Tweener fund,

one of the most active funds in the Southeast, and at times in the US. This fund makes 10-15 investments per quarter

– often the first institutional capital into a young business.

Primordial

Ventures, Jurassic Capital, Cofounders Capital, IDEA Fund Partners and others

are extremely active across our region. And new funds are being launched

regularly as more and more people consider venture investing as a part of a

diverse investment portfolio.

I

was unable to find exact financial data, but in my research I was unable to

find any region with more “first money in” style capital than North

Carolina. San Francisco and New York

certainly can write bigger checks. But in a world where AI will continue to

shorten time to market, reduce cost to first prototype and allow founders to

build with smaller teams, the amount of money needed to launch comes down

dramatically. Late stage capital becomes unimportant. Regions with early,

risk-tolerant capital are well-positioned.

What

differentiates this ecosystem is not sheer dollar volume, but alignment.

Much

of the Triangle’s early-stage capital is deployed by investors with deep

operating backgrounds in software, life sciences, cleantech, advanced

manufacturing, and data-driven systems. These investors understand

commercialization risk, are comfortable with long development timelines, and

often co-invest alongside non-dilutive capital sources such as SBIR, STTR, and

NC IDEA and NC Innovation-supported programs.

Compared

to peer regions, North Carolina’s advantage lies in density rather than hype.

Founders can access investors, customers, researchers, and pilot environments

within a single geography. Capital circulates locally. Relationships compound.

This

does not eliminate the need for larger-scale public investment mechanisms. But

it does mean the foundation is stronger than it appears from headline venture

rankings alone. The Triangle, in particular, has become a place where

early-stage companies can be formed, financed, and validated without

immediately relocating to the coasts.

That

is a real advantage worth building upon deliberately.

Defense and dual-use: A durable growth engine

If entrepreneurship represents the how of future growth, defense

represents one of the clearest wheres. No segment of the market is

expanding more consistently or at greater scale than defense and national

security–related technology. The Department of Defense accounts for more than

half of all federal R&D spending, and defense budgets remain at historic

highs.

Increasingly, that spending is directed toward software, data systems,

autonomy, cybersecurity, logistics optimization, advanced materials, and space.

And more specifically, there is an investment priority on defense technologies

that also power commercial markets.

North Carolina’s position here is unusually strong. The state supports

more than 3,600 defense contractors, over 575,000 defense-supported jobs, and

an estimated $65–70 billion in annual economic impact tied to defense activity.

It is one of only two states — along with Hawaii — where every branch of the

U.S. military operates.

Geography reinforces this advantage. North Carolina’s central position

along the East Coast, its deepwater ports, and a highway system originally

designed for military deployment efficiency make it a natural logistics and

operations hub. The state’s diverse terrain, from the highest peaks east of the

Mississippi to extensive coastal environments, supports testing and training

environments that few other states can match.

Compared with peers like Virginia, South Carolina, and Tennessee, North

Carolina offers breadth. Virginia’s defense ecosystem is deeply tied to federal

procurement and policy proximity. South Carolina and Tennessee host important

installations. North Carolina combines scale, diversity, infrastructure, and

industrial adjacency, which is a rare mix.

Defense is no longer a niche sector. It is one of the world’s most

important technology customers. It is important that our region organizes

around that reality to capture long-term value.

Entrepreneurship as economic infrastructure

All of this leads to a simple conclusion. Entrepreneurship is not

culture. It is infrastructure. Regions that make it easier for people to start

companies that survive the early years consistently outperform those that do

not. They create more middle-class wealth. They diversify their economies

faster. They distribute opportunity more broadly.

In an era when automation is compressing traditional job ladders,

economic agency increasingly depends on the ability to create work

rather than simply find it. States that invest in entrepreneurship through

translation support, capital access, and market-aligned demand are best

positioned for broad economic prosperity across their populations.

Designing the next phase of growth

Measured honestly, the State of the Region in 2026 is neither dire nor

complacent.

North Carolina is growing, but unevenly. It is innovative, but

constrained by translation and capital gaps. It is exceptionally well

positioned for defense and dual-use technology, yet under-organized for

execution at scale.

In a future where AI will increasingly automate workflows that once

were conducted by humans, we need to adapt. There will never be a shortage of

ways to make money. But there may be fewer and fewer “generic jobs” within

industry. Now is a pivotal time to adapt our investment strategy.

As you think about how you can be a partner in this transformation, or

how your organization should behave as we work through 2026, here are a few

points to consider:

●

Job

creation should outweigh job attraction

●

Creative

and people skills outweigh technical skills

●

Augmenting

humans with AI is more powerful than standalone AI systems

●

Workforce

development must prioritize teaching entrepreneurship

●

We must

invest in creating new companies instead of attracting existing ones

●

The

future is won by solving new problems instead of scaling old ones

With

this context, I am excited to announce that NC IDEA and the Wireless Research

Center have executed a joint venture agreement to bring the two organizations

closer together.

For

20 years, NC IDEA has been providing nondilutive capital to startups and

funding entrepreneurial support organizations, including RIoT. Since 2010, the

Wireless Research Center has been advancing technology and helping startups to

build the Data Economy. When RIoT launched in 2014, our first seed capital came

from NC IDEA.

After

years of being two organizations, working across contract boundaries, it made

sense to unite under our shared mission and complementary skill sets. With this

joint venture, Tom Snyder and Rachael Newberry will formally join the NC IDEA

team, and bring RIoT’s accelerator and entrepreneurial programs under the NC

IDEA roof. At the same time, the Wireless Research Center is launching RIoT

Labs to add focused support for defense and defense dual-use technology

development and commercialization.

We

want to capture the dual opportunity of the major economic trends I outlined

above. We believe this joint venture positions us to become the most

entrepreneurial-supportive state in the US and also the leading state for

defense sector innovation and commercialization.

This

is a new chapter for the North Carolina ecosystem and I could not be more

excited for the future we will create together. Our efforts remain focused such

that all people can reach a point of economic security, knowing that above all

else, economic security leads to health security, food security, housing

security, safety, education and ultimately to more peaceful and prosperous

communities.