The Australian government sees the value of generative AI across local, state and federal governments. However, unseasonably long spending restrictions and concerns over automation disasters are slowing AI adoption, at least in terms of citizen-facing solutions.

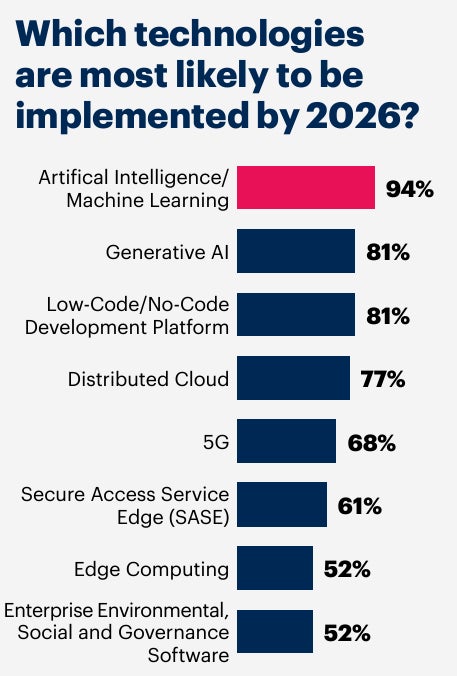

According to a Gartner survey of CIOs across APAC governments (with Australia sitting right in the middle of the trend), AI/machine learning and generative AI are the two biggest priorities to be implemented by 2026 (Figure A). And yet, other pressures are making government agencies hesitant to adopt AI in areas that the Australian government considers to be critically important.

Figure A: The technologies that CIOs in APAC governments expect to implement by 2026. Image: Gartner

For example, while the Gartner research shows that 84% of CIOs consider investment to excel in the citizen experience to be a top priority (Figure B), less than 25% of government organisations will have generative AI-enabled citizen-facing services by 2027.

Figure B: The top three priorities for APAC government agencies. Image: Gartner

Figure B: The top three priorities for APAC government agencies. Image: Gartner

The Australian government’s disconnect between a desire for AI implementation and the ability to deliver

As Gartner VP Analyst Dean Lacheca said in an interview with TechRepublic, there is public scepticism around public large learning models, with concerns about privacy, security and data readiness impacting the speed of AI adoption. This is a particularly sticky issue in Australia, where automation, including AI, within government services has caused material harm. Consequently, there is an inherent distrust for any applications that are perceived to automate interactions with citizens across the whole of government.

Most noteworthy, while it was not an application of AI, the “Robodebt” scandal that so significantly impacted Australians resulted in a Royal Commission following a change of government. The automation that was at the centre of that controversy has made many government agencies hesitant to announce to the public that they’re exploring AI use.

“That association with automation isn’t outright voiced, but the underpinning sentiment is that government agencies are aware that there’s a lot of reputational risk here if they get it wrong,” Lacheca said. “There is some frustration at the executive level as to why they can’t move faster in the AI space, but there’s validity in the conservative approach to the first few steps and to fully think through the use cases.”

Tightening budgets have an impact of the Australian government’s AI adoption, too

This conservatism is being further compounded by lengthy austerity in government spending on IT, which Lacheca said is impacting the kinds of projects that are being greenlit. There is an understanding of the need for investment, he said, but the leaders that greenlight projects have a total focus on productivity, effectiveness and a fast ROI.

With AI being a new area for many CIOs and their teams in government, and AI requiring transformation and new approaches to technology, finding and then articulating the right projects that can deliver quickly can be challenging.

“Because the goals of projects tend to be relatively modest, in seeking that quick ROI, there is also an education piece that the IT teams need to undertake with the executive,” Lacheca said. “We’re often hearing elements of frustration along the lines of ‘my teenage son is at home using ChatGPT, why are you making this more complicated for us?’

“So managing expectations of what can be achieved with the technology given the focus on immediate goals and overcoming the hesitancy around citizen-facing services is part of the process with government adoption of AI right now.”

More Australia coverage

Gartner’s solution: Focus on delivering internal applications first

According to Gartner, the solution to these challenges with adopting AI is to start by delivering applications that are not citizen-facing but can support productivity gains within the internal organisation. The “low-hanging” fruit allows government agencies and departments to avoid perceived risks associated with AI in citizen-facing services, while building the critical knowledge and skills that are needed to develop more ambitious AI strategies.

Agencies should also build trust and mitigate associated risks by establishing transparent AI governance and assurance frameworks for both internally developed and procured AI capabilities, Gartner’s guidance adds.

“There is a lot that government organisations need to do to take steps into AI,” Lacheca said. “For one use case, for example, an agency might want to summarise a set of data, but that data contains personal information and perhaps doesn’t have the right metadata tags. They might want to parse that out.

“Others are looking to cloud solutions where the data never leaves their world, and others are looking to the ‘stained glass’ approach which will ensure a level of obfuscation of the data on the way out as a strategy for protecting the privacy. There’s a lot of architectural maturity in how AI strategies are implemented, which is why organisations should be looking to develop these capabilities before applying them to public-facing deployments,” he added.

How partners should look to engage Australia’s government about AI

These internal tensions will also affect the partners of the Australian government’s agencies. The appetite is there for AI, but getting the cut-through and helping to deploy solutions means understanding that the austerity in government budgets is unusually long and the conservatism about potential consequences is more sensitive than might be the case in other sectors.

“The next steps that government could take will probably be a lot slower than maybe some of the commercial counterparts, because their risk appetite has to be different,” Lacheca said.

For IT professionals working in and in partnership with government agencies, Gartner’s recommendations on how to step forward with AI come down to being able to demonstrate a fast ROI with minimal risk to public data and interactions. The partners that can deliver this will be in a strong position when the government later begins accelerating adoption to meet their longer-term ambitions.