Last month, Patch announced it was publishing AI-generated newsletters in 30,000 communities across the U.S. These newsletters scrape from local news sites, social media groups, and official town websites, then use large language models (LLMs) to select the most relevant headlines and draft story summaries. The final product is a daily or twice-weekly email round up, with link outs to five articles and a list of upcoming events.

It’s local news aggregation, but fully automated, and on a scale that until recently was not possible for the hyperlocal news network. In an Axios article announcing the expansion, Warren St. John, the CEO of Patch, clarified the AI newsletters supplement its “85 full-time newsroom staffers and won’t replace the work of any of Patch’s journalists.”

What the Axios story doesn’t mention is that Patch had previously tried to do this work with humans. The “curated newsletter program,” which ran for more than two years before it was shuttered in November 2023, had a similar goal of bringing aggregated local newsletters to towns across the country — using contractors, not AI.

“Patch was trying to create a community newsletter and bring people from that community on board to make it more personalized,” said Kristen Burke, who worked as an aggregator, or curator, as Patch called them. From the fall of 2021 to the fall of 2023, Burke wrote a daily newsletter about Dunedin, a hub for snowbirds on Florida’s Gulf Coast.

Curators were freelance, and some had never written professionally before, but they filled holes in Patch’s network of local sites. Each day Burke sorted through news stories about Dunedin and scoured social media events, synthesizing it all into a conversational email. Alongside links to articles, she notified readers of changes to recycling pick up days, plugged volunteer hurricane recovery groups, and spotlighted band nights at local dives.

As the Dunedin newsletter audience grew to over 9,000 subscribers, residents started recognizing Burke around town. Some knew her simply as “the Patch lady.” “People felt like they were connected to me,” she said. “It’s a very small town, we’re a tight-knit community, so it was easy to talk to people about it, and if they were business owners, they would usually reach out to me about advertising opportunities.”

As the program ramped up in 2021 and 2022, Patch brought on three editors to work with the curators, all overseen by a dedicated project manager. Near its peak in September 2022 the program produced 85 daily newsletters across the country, for towns including Patchogue, New York; Round Rock, Texas; Huntsville, Alabama; and Myrtle Beach, South Carolina.

In theory, these newsletters were similar to the AI-generated product that now arrives in the inboxes of over 400,000 Patch subscribers across the country, only on a much smaller scale, and each with a human touch.

Despite success in markets like Dunedin, Patch never found a sustainable business model for its curated newsletters. “There were certain communities where we couldn’t sell an ad to save our lives, where it just wasn’t taking, we weren’t getting a lot of subscribers,” said Simone Wilson, a former product manager at Patch who oversaw the program in its final months. “We had been turning those newsletters off throughout the experiment.”

On November 10, 2023, Patch shuttered the program and its remaining newsletters altogether.

“The reason we discontinued the curator program was simply that the economics did not work,” said St. John, pointing to a slumping real estate ad market at the time and challenges getting curators to sell ads to local businesses. He insisted that curators were not fired because of Patch’s AI adoption, but confirmed the company first started testing the use of LLMs in April 2023, six months before the curated newsletter program ended.

For years at Patch there had been a mantra, an aspiration as the network scaled across the country: “Patch everywhere.” Multiple former Patch employees told me St. John would reference this moonshot goal in team meetings. “There was this idea where we would open up a Patch community in every incorporated town in America,” said Madison Feser, a former project manager, who oversaw the curated newsletter program before she left Patch in April 2023.

Patch never planned to hire a full-fledged reporter in every town in America, but the experiment posited that aggregation could be outsourced to community members beyond the newsroom. Curated newsletters were one step toward this goal, but in the end human aggregators couldn’t get Patch everywhere. There was still a chance that AI could.

Days after the final newsletters were sent out on November 10, 2023, a fully automated Patch newsletter arrived in the inbox of Burke’s former readers in Dunedin. Burke’s byline had been replaced with a new one: “Patch AM Team.”

That “what’s happening locally” feel

Patch never required its curators to have journalism experience. Old job listings say the company was looking for community members with “a strong understanding of the local news and media landscape” and someone who loves “sharing the inside scoop with others.”

“I saw the ad and was like, oh gosh, I know everything about my community,” said Joanne Gallo, the former curator for Mineola, New York. Gallo had worked as an editor for 30 years and has a master’s degree in journalism from New York University. Even though those credentials weren’t required, Gallo said she relied on them in her work — “news judgment, of course, and good writing and editing.”

When Gallo joined Patch in 2021 she knew the company had been investing in automation. The team at Patch Labs, the company’s internal tech incubator, had custom-built a tool that took headlines and article links from local outlets in a given market and slotted them into a CMS template. At the time, the tool was pitched as a way to boost efficiency.

Curators were expected to produce each daily newsletter in one to two hours, though some averaged closer to three. Each curator was paid between $15 and $25 per edition, plus double on holidays and weekends. “When it was paying $20, I didn’t want to spend more than an hour on this thing. That’s just realistic,” said Gallo. “So yes, the links were helpful, not that I had to use them, or always did, but it was a base from which to start.”

Curators were expected to produce each daily newsletter in one to two hours, though some averaged closer to three. Each curator was paid between $15 and $25 per edition, plus double on holidays and weekends. “When it was paying $20, I didn’t want to spend more than an hour on this thing. That’s just realistic,” said Gallo. “So yes, the links were helpful, not that I had to use them, or always did, but it was a base from which to start.”

This early automated tool had flaws. It pulled in news stories from completely different towns, it indexed heavily on obituaries and crime stories, and it failed at times to surface stories everyone was talking about, according to multiple curators. Every curator I spoke to said they ignored the automated draft it generated, or only used it sparingly.

“I used to call myself the town Googler,” said Jeri Karges, who curated newsletters for three towns in California. Curators like Karges had always been offered commission on local ads sales, but as the program ramped up, Patch increasingly pressured them to not only write and research, but to pitch ad spots to local businesses. After Karges’ Sacramento newsletter was shut down, the reason came into focus. “It was pretty clear that they were spending more than they were making on these newsletters,” she said.

Other curators made similar calculations, including Ashley DeMello, who wrote newsletters for Beaverton, Oregon; Merrick, New York; and Irving, Texas. “I knew that it was on a [limited] timeline from the beginning because I knew how much they were paying me, and I knew what my readership was,” she said.

“The ad revenue was not matching what it cost to create the newsletters,” said Wilson, the former product manager.

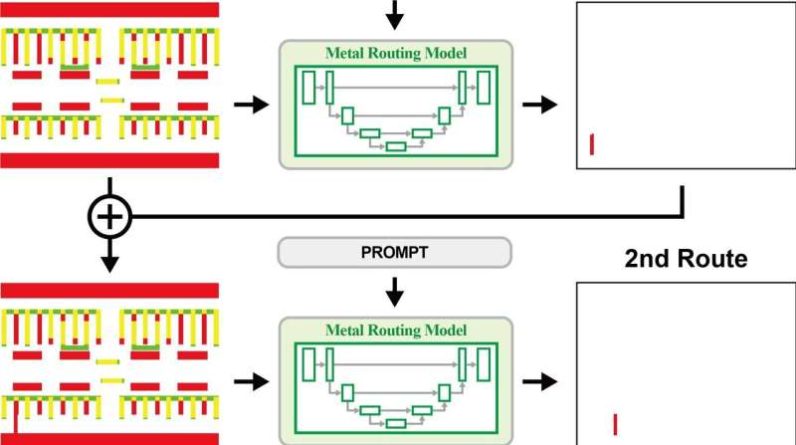

Unbeknownst to most curators, Patch was already experimenting with fully automated newsletters in other markets, according to Wilson. Patch had long published automated newsletters featuring its own stories, but increasingly Patch Labs was trying to pull in outside sources to its newsletter without any human intervention. In the final months of the curator program, the company began integrating LLMs into these tests, including using OpenAI’s API.

“We saw interesting stuff in the data that sometimes community members didn’t care” that the newsletters were AI-generated, said Wilson, referring to thumbs up, thumbs down reader surveys that ran alongside these newsletter tests. “They would rate those newsletters the same as they would” the work of a local person.

Wilson was not directly involved in the decision to end the curator program, but she said that given these successful tests the writing was on the wall. “It made it hard to justify continuing a program that was essentially not working. We weren’t meeting our goals,” she said. “Obviously, the costs are way lower for AI newsletters.”

Wilson was not directly involved in the decision to end the curator program, but she said that given these successful tests the writing was on the wall. “It made it hard to justify continuing a program that was essentially not working. We weren’t meeting our goals,” she said. “Obviously, the costs are way lower for AI newsletters.”

In October 2023, Wilson emailed the remaining curators announcing the end of the program. “The product department (including my role), as well as the curated newsletter programs that you’re part of, are being shut down soon, as they are no longer a viable part of the business,” she wrote. All the curators’ contracts would end on November 10.

Days before Burke published her final Dunedin newsletter, a local advertiser forwarded her an email sent by a sales manager at Patch. The manager told the advertiser a different story — the Dunedin newsletter would continue publishing, using full automation.

“The Dunedin newsletter will stop being written by the current writer effective next week,” wrote the manager. “Over the last few months we’ve been experimenting with an automated newsletter sent out to our readers in other towns, and the response we’ve received has been overall positive. Unfortunately, the economics for a human-created newsletter is not working at this time, and we’ve made the decision to switch all of our remaining newsletters to this new automated version.”

Burke felt that Patch had lied to her. “If you’re gonna fire everybody and replace them with AI, you can at least be honest,” she said.

Other curators only learned about the automated newsletters because readers reached out to complain about a drop in quality. The same week the program ended, Karges received a text message from a local city council member: “Any idea who is running Roseville Patch? It seems automated. There’s no longer a ‘what’s happening locally’ feel to it.”

“Even at the time, I was worried about the possible perception that [writers] were being replaced by AI. I really do not see that as what happened, but the optics of it made me wince,” said Wilson, who was also let go as part of the project’s termination. “Whenever you have people involved, there’s hopes and dreams and feelings and community connection. That was always a hard part about working for a company that dealt with so many communities.”

St. John clarified that not all the newsletters written by curators switched to full automation immediately, and said the system was still in development when the curator program ended. “This automated thing, at the time the curator program ended, was not ready for prime time,” he said. “I think we were all quite skeptical at the time that without a great deal of work that was actually going to be a viable option.”

In the months that followed though, Patch leaned hard into its burgeoning AI technology and used reader feedback to try to smooth over several quality issues flagged by readers. In the summer of 2024, the company launched the refined system in every town across Georgia and Virginia, an official pilot of its “Patch AM” morning newsletters. By earlier this year, they’d expanded the newsletters to tens of thousands of towns nationwide.

In the months that followed though, Patch leaned hard into its burgeoning AI technology and used reader feedback to try to smooth over several quality issues flagged by readers. In the summer of 2024, the company launched the refined system in every town across Georgia and Virginia, an official pilot of its “Patch AM” morning newsletters. By earlier this year, they’d expanded the newsletters to tens of thousands of towns nationwide.

Patch is not the only digital publisher that sees local news aggregation as an editorial task primed for automation. Earlier this year I uncovered a network of AI-generated local newsletters operating in over 350 towns across the country using a similar underlying system. Sites aggregating local events by scraping social media posts have also begun popping up in small towns across the U.S., including one site I covered in Bentonville, Arkansas.

“In an age of AI, when LLMs are vacuuming up content, the half life of information is much shorter than it ever was before,” said St. John, arguing that AI aggregation allows Patch to consolidate its newsroom and grow the number of full-time reporters and editors on its staff doing original journalism. “If you’re aggregating today as part of your core offering that’s got very limited benefits, the benefit is in finding information no one knows.”

Patch’s newsletters are finally everywhere, or close to it, but not every former employee I spoke to saw this AI strategy as furthering the network’s local news mission. “Patch everywhere sounds great on the surface, but the pushback is it’s kind of like opening 1,000 stores. You can have 1,000 storefronts, but without the products inside it, it’s just a storefront,” said Feser, the former Patch project manager. Without a real person at the center with real ties to the community, what is Patch actually offering in 30,000 towns?

“I would agree that there is information there. And [AI newsletters] still bring local news in,” said Feser. “But to me, it’s missing a bit of what makes local news local.”