Electric Nightmares is a four part series about generative AI and its use in video games. In Part 1, Our Generation, Mike Cook takes a look at what people mean when they say ‘generative AI’.

If you’ve ever tried to play a hardcore RPG that’s way above your brain’s pay grade, or got lost in tutorials that use complicated words and bizarre jargon, then you’ve probably felt right at home reading headlines about AI recently. Why are people angry that this character has seven fingers? Why does Nvidia want me to talk to a robot about ramen? Why is everyone saying AI is smart when it still can’t manage its Classical Era luxury resource economy in Civilization properly? In this new series, we’re going to explore what ‘generative AI’ is, why it’s arrived now in the games industry, and what it might mean for people who make, write about and play games in the future.

In my day job, I’m a Senior Lecturer at King’s College London’s Department of Informatics, where I lead a research team dedicated to studying how AI might change creativity and games. You might have seen some of my research on RPS before, such as the game-designing AI Angelina. I’ve been doing this research since 2011: before AI Dungeon launched on Steam; before OpenAI Five took on DOTA 2’s world champions; before Lee Sedol’s historic loss to DeepMind’s AlphaGo. When I started studying AI as a PhD student, it was a field very few people were interested in, and the idea of studying AI for games or creativity was a niche within a niche. Since then, I’ve watched as public opinion has gone from one extreme to another, and now the main problem I face as a researcher isn’t people underestimating what AI can do, but rather overestimating it. In this four-part series, we’re going to try to find that middle ground between the extremes, and from there see what’s really on the horizon for the games industry.

First, an important question: what does ‘generative AI’ mean? That’s something even I’m not always sure about. As AI has become more popular, we’ve lost our grip on what most of its terminology’s come to define. Even the term ‘AI’ itself has lost all meaning as it’s been applied to every technology product in existence. Did you know you can get gamer headphones with “AI Beamforming” technology in them, for example? Generative AI might be especially confusing for people who play PC games, too – weren’t games like Spelunky and Minecraft using procedural generation to make their levels and worlds back in 2010? Heck, weren’t Rogue and Elite using it in the 1980s? Isn’t that generative?

Spelunky 2 is a 2D platformer that uses procedural generation to present new challenges to its players. | Image credit: Mossmouth

Today, ‘generative AI’ most often means a machine learning system that has been trained to produce some kind of creative content, especially artistic outputs like art, music or writing. These AI systems can usually be ‘prompted’ by writing a request in plain language, which is where we get famous systems such as Midjourney, which you can get images from simply by describing what you want with words. Using AI to create art or music isn’t new. In fact, it stretches back decades, long before my PhD. But it’s shot into the popular consciousness now that machine learning models have provided simple interfaces and higher-fidelity results. New AI results went viral from time to time on social media, then they popped up as little demos you could try yourself, and before long it began to feel like a product. Then, suddenly, it was a product.

It might seem like generative AI is already taking over the games industry. Earlier this year, GDC released their annual State of the Industry survey, in which they claimed that 31% of surveyed developers used generative AI in their workplaces, and 49% of studios were using it. But ‘generative AI’ can describe anything from people using AI image generators to create every single art asset in their game, down to people who just use ChatGPT to write their emails. Generative AI is not a single concept, and using it for one area – such as programming – might feel and work very differently to using it in another – translating dialogue, say. Regardless of any studies, headlines or big press releases, generative AI is a big, messy, controversial idea, and it won’t affect all parts of the games industry in the same way.

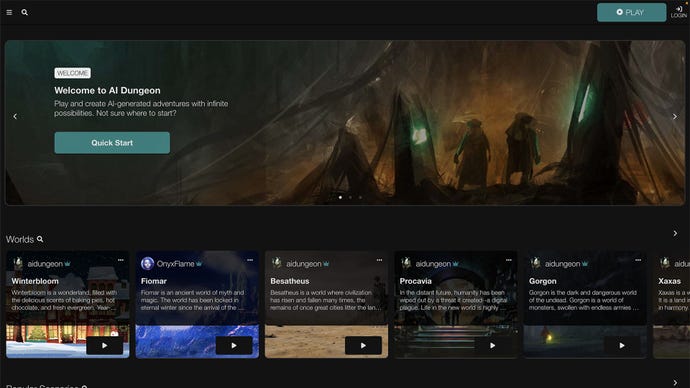

To help you think about some of these differences, I’ve got some suggestions for new words we can use to talk about generative AI systems. The first is ‘online’ versus ‘offline’ systems (which I’m borrowing from research on procedural generation). Online systems generate content while you’re playing the game – AI Dungeon is an example of an online generative AI system, because it writes in real-time while you’re playing. Offline systems are more for use during development, like the use of generated AI portraits in the indie detective game The Roottrees Are Dead. Portraits and other artwork were generated using Midjourney and added to the game, but the game itself doesn’t generate anything. As you’d expect, online systems are a lot riskier because developers can’t test every possibility in advance, but they can also lead to more exciting and innovative game designs. Offline systems are easier to test, secure and validate, which might make them more popular with big studios who can’t afford to take risks with unpredictable technology in live games.

Released in 2019, AI Dungeon is a text-based, AI-generated fantasy sim that lets players create and share adventures using custom prompts. | Image credit: Latitude

Another way we can categorise generative AI systems is between “visible” and “invisible” systems. Visible systems produce content that you directly feel the effect of – things like art or music – while invisible systems generate content that the average player might not be as aware of. For example, some programmers use GitHub Copilot, a generative AI system that can write small sections of program code. If someone used Copilot to write the multiplayer networking code for your favourite MMORPG, you almost certainly would never hear about it (unless something went wrong). The same goes for many aspects of game development that we don’t necessarily see directly – if the finance department uses ChatGPT to compile their monthly reports, for example, or if concept artists produce some pre-alpha artwork using DALL-E. The visibility of a generative AI system may be increasingly important as backlash against the use of AI tools rises, because developers may feel safer employing generative AI in less visible ways that players are less likely to feel the presence of.

The third category, and maybe the most important one, is whether the AI is “heavy” or “light” – thanks to my colleague and student Younès Rabii for suggesting the names for this one. Lots of the most famous generative AI tools, like ChatGPT or Midjourney, have been trained on billions of images or documents that were scraped from all across the Internet; they’re what I call heavy. Not only is this legally murky – something we’ll come back to in the next part of this series – but it also makes the models much harder to predict. Recently it’s come to light that some of these models have a lot of illegal and disturbing material in their training data, which isn’t something that publishers necessarily want generating artwork in their next big blockbuster game. But lighter AI can also be built and trained on smaller collections of data that have been gathered and processed by hand. This can still produce great results, especially for really specialised tasks inside a single game.

The generative AI systems you hear about lately, the ones we’re told are going to change the world, are online, visible and heavy. We’re told that generative AI is going to live inside every video game, changing its look, mechanics and story in real-time, and use big names like ChatGPT to make it happen. The history of technology in games tells us that’s probably not going to be how it plays out. The technology that will likely become persistently useful will be offline, invisible and much lighter. As an example, we can look at the history of pre-2015 generative technology in the games industry. Despite all the potential and excitement around procedural generation, the most enduring and widespread tool in the industry is SpeedTree, a very specialised tool for generating trees and other flora, used mostly by environment artists for over twenty years. You may not have even heard of it.

But that kind of hindsight is still a long way off for generative AI, and in the meantime there’s a storm of court cases, hopeful start-ups and confused game design pitches for us to weather. Tomorrow, we’ll sail headfirst into the choppy waters of ethics and the law. Until then, keep counting those fingers, and don’t talk to any strange robots.