AppleInsider may earn an affiliate commission on purchases made through links on our site.

Bard is ostensibly designed to leverage Google’s massive advantage in search with an AI chatbot. The problem is, Google’s offering is worse in nearly every regard versus Microsoft’s Bing.

A sign that a technology is a potential game-changer is if you have competition in that market. Just like the ongoing battles of Windows vs Mac, iPhone vs Android, and Zoom calls vs IRL family reunions, there’s now one in the AI chatbot space.

Microsoft was the first to move, with its ChatGPT tie-up resulting in “the new Bing.” But Google wasn’t far behind in announcing its own vision, in the form of Google Bard.

After an initial introduction in February, Google Bard started to be rolled out to users on March 21, enabling interested parties to see the search giant’s work in action.

At first glance, it seems that it’s going to be a close race. Sadly, it’s because Google Bard’s not really that much better than Microsoft’s “new Bing.”

The same, but different

Much like ChatGPT, Google Bard is a conversational AI interface that takes a user’s request and, using its available resources, produces a result.

The Language Model for Dialogue Applications (LaMDA) is the conversational AI model, which Google says is capable of “fluid, multi-turn dialogue.” In effect, it’s Google’s specific system for predicting the most appropriate word to use next in a sentence or statement.

Just as Open AI’s system uses a large base of information to determine what those next words should be, Google Bard relies on the search giant’s knowledge graph.

There’s naturally going to be a difference in the knowledge base, as the “new Bing” uses Bing’s data archive while Google Bard uses Google’s vast collection. However that’s only half the battle.

The other is how the chat system is ultimately implemented, and in the type of results it offers.

Easy onboarding

One of the first curiosities of New Bing was Microsoft’s offer for user to jump the queue. If you agreed to set Microsoft’s services as default, you could jump up that waitlist.

Google didn’t go down that route. Instead, you were asked to sign up for a waitlist, and that’s it. No extra hoops to jump through, no bribing the bouncer, nothing.

Indeed, Google also avoids taking another odd route that Microsoft went for, which was to limit access to the Edge browser. And even then, only on desktop, until Microsoft later introduced the chatbot to its Bing app.

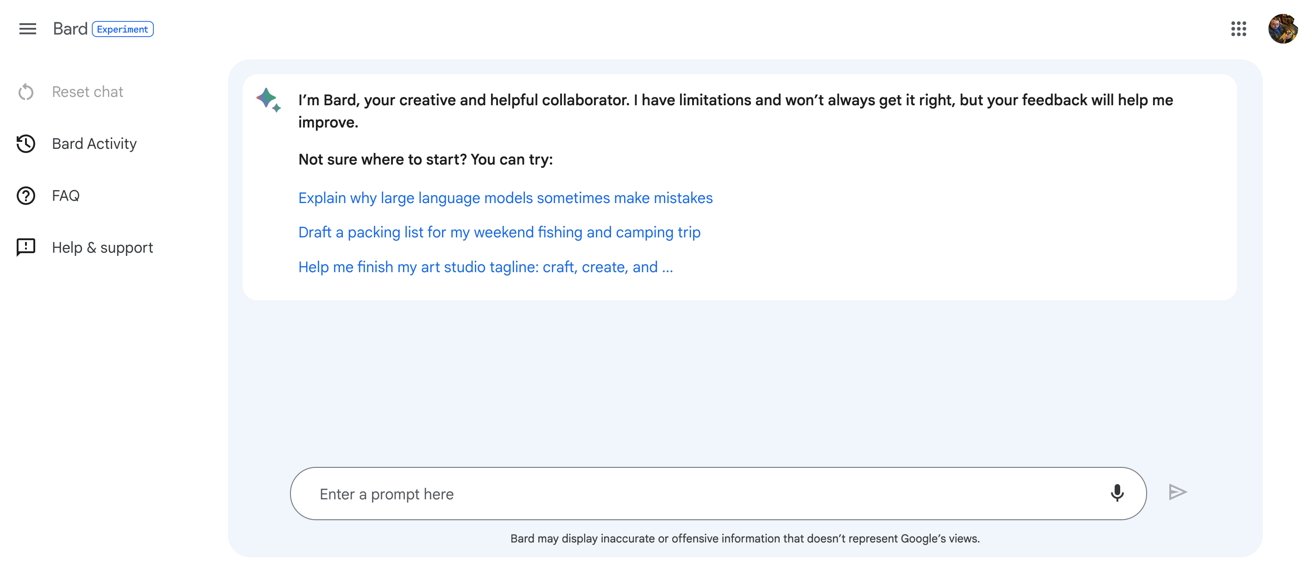

With Google, you could use Bard on a signed-in Google account on any browser, even on mobile devices.

This writer started using Google Bard in Chrome on iOS, which wasn’t possible during Bing’s testing.

There are restrictions, but they are reasonable. For a start, you can only sign up with a personal Google Account that you manage, not a Google Workspace one.

You also need to be aged 18 or over. Given the potential for unexpected responses to queries, this is probably a safe route.

Lastly, it’s only available in the U.S. and U.K. in US English. That again makes sense, especially if Google is trying to shake out problems in English before moving onto other languages.

While Microsoft was cautious and used it as a way to get ahead on user’s systems software-wise, Google went down the road of being more open.

Cautionary statements

The world is familiar with the horror stories of using ChatGPT, including inaccuracies in responses and the unusual statements it came out with under certain methods of questioning.

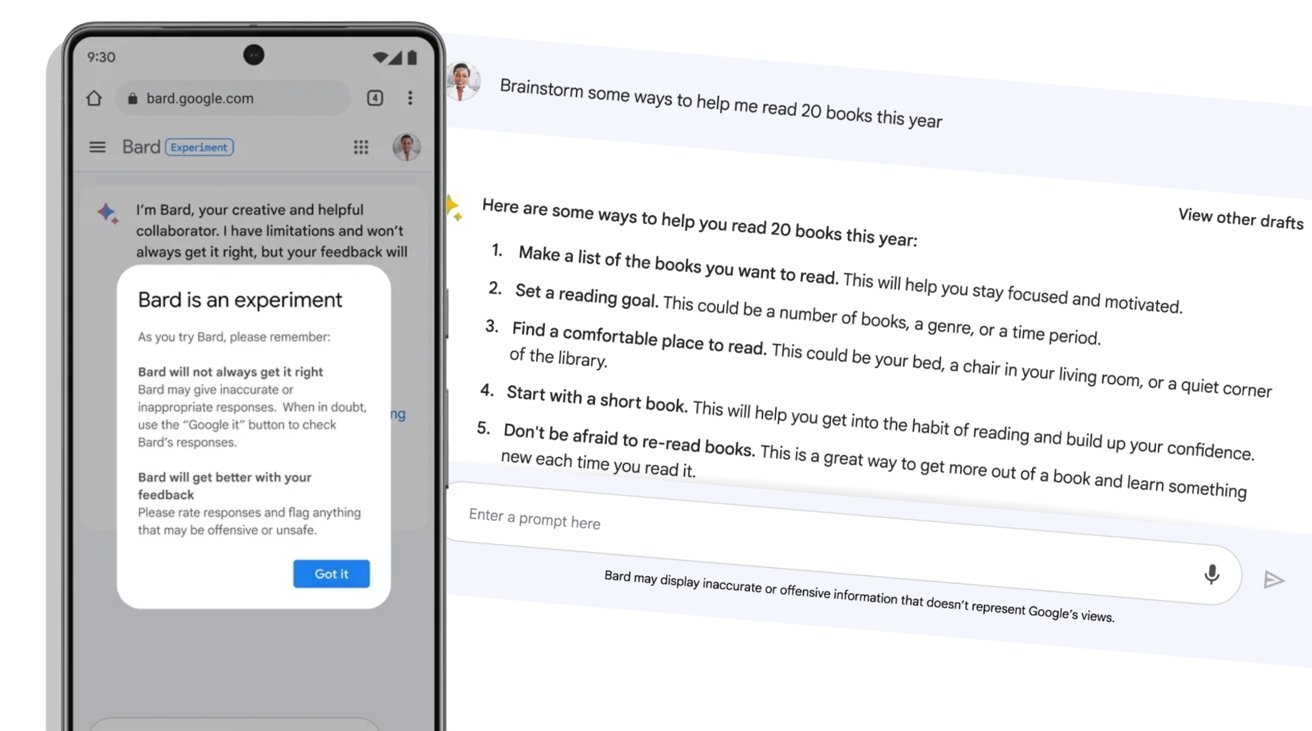

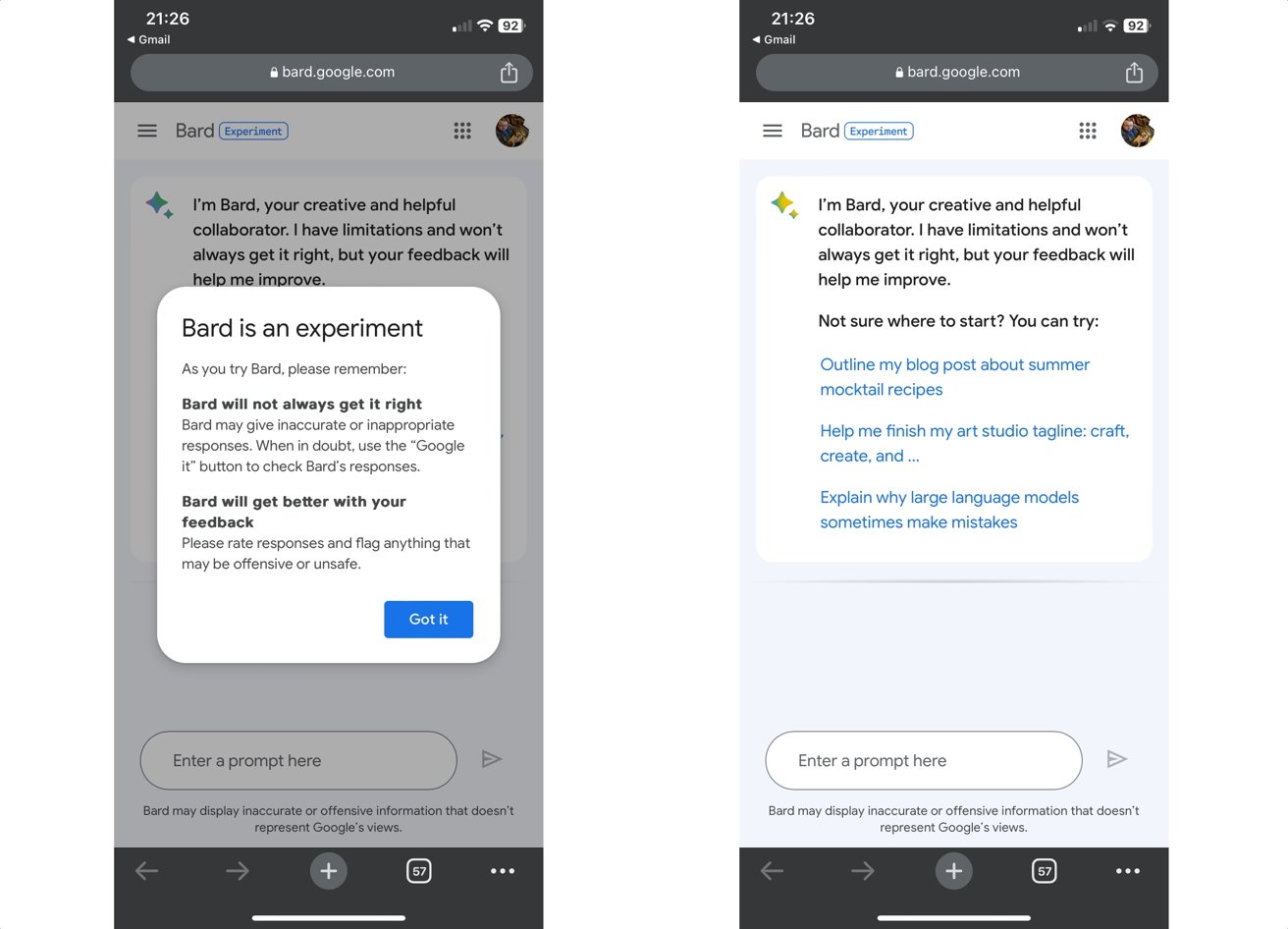

From the gate, Google’s taking things very cautiously, with various notifications that it’s a work in progress and can get things wrong. Think a digital version of “Objects in the rear view mirror may appear closer than they are.”

The FAQ says your Bard data won’t be used for ads. Yet.

On being granted access, an initial pop-up warns “Bard will not always get it right,” that it could give “inaccurate or inappropriate responses,” and to use the “Google it” button to double-check answers.

At the bottom of the main page, right under the text entry box, there’s another statement advising “Bard may display inaccurate or offensive information that doesn’t represent Google’s views.”

A handy FAQ page includes “Does Bard give accurate and safe responses?” as a question. Amusingly, in answering if Bard is “able to explain how it works,” Google says Bard can “hallucinate and present inaccurate information as factual,” and that Bard “often misrepresents how it works.”

Safety controls and mechanisms “in line with our AI Principles” are also apparently in place.

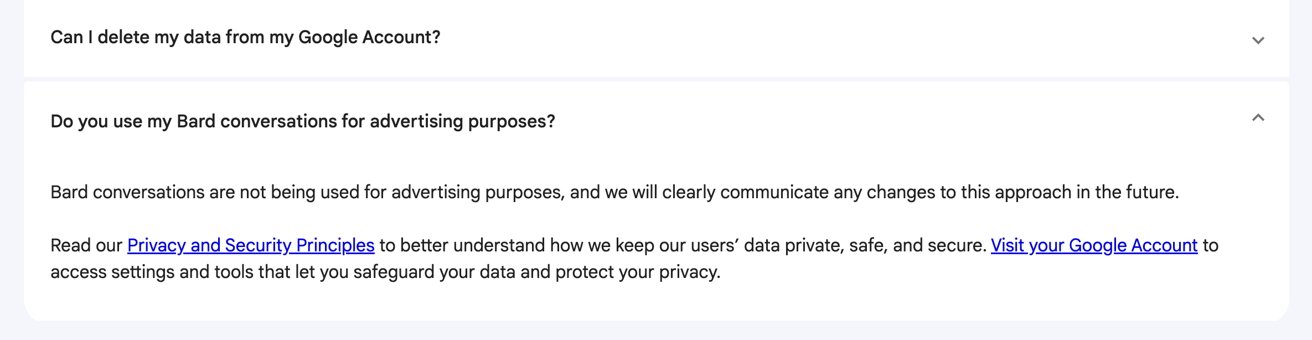

To ease those fearful of mass data collection, Google also answers questions about terms of service, what data is collected (general location based on IP address and collections of conversations are the main ones), who has access to Bard conversations, if users can delete data, and if Bard conversations are used for advertising purposes.

On that last point, they aren’t for the moment, but Google will “clearly communicate any changes to this approach in the future.”

Citations needed

At face value, using Google Bard is similar to how you would use Bing’s ChatGPT, except in the standard Google UI aesthetic. But the first real difference is in when you actually ask a question.

After being given the first response, you’re also provided with two other draft answers, which you can also view. This can be handy for instructional queries, or requests where you ask Bard to be creative, without needing to make the same request a second or third time.

The FAQ says your Bard data won’t be used for ads. Yet.

Below the result are a couple of interface buttons. Thumbs up and thumbs down are used to give feedback on whether it was a good response to the query, while New Response tells Bard to try again.

A fourth button, “Google it,” brings up links to search for related topics. This is very helpful if you want to double-check Bard’s work.

You may end up using that button a lot, if you want to find out where Bard got its responses. While Bing is more than happy to offer citations for where it gathered data for its responses, Bard holds off from doing that.

Sometimes, sources do appear, but very rarely. The FAQ clarifies that citations are given if Bard directly quotes at length from a webpage.

A very rare citation.

Given the abundance of citations that Bing offers in comparison, seeing this on Google’s version is more than a little offputting. For a company that prides itself on offering the information and where to get more, it is quite a change in policy.

We did discuss during our Bing test that citations offer a way for the public to get to sources, and for sources to ultimately earn revenue for what is put out to the Internet, and that more needed to be done. There seems to be a lot more that’s required on Google’s side in this instance.

Of course, users could tap “Google it” and get the full-fat search experience, and get to see those actual sources. Except they probably won’t, as they will have already received the information they need.

Bard play

The actual use of Google Bard is pretty similar to how you’d expect ChatGPT conversations to go. Except it’s all tinged with Google’s knowledge archives and attempts to add guardrails to the experience.

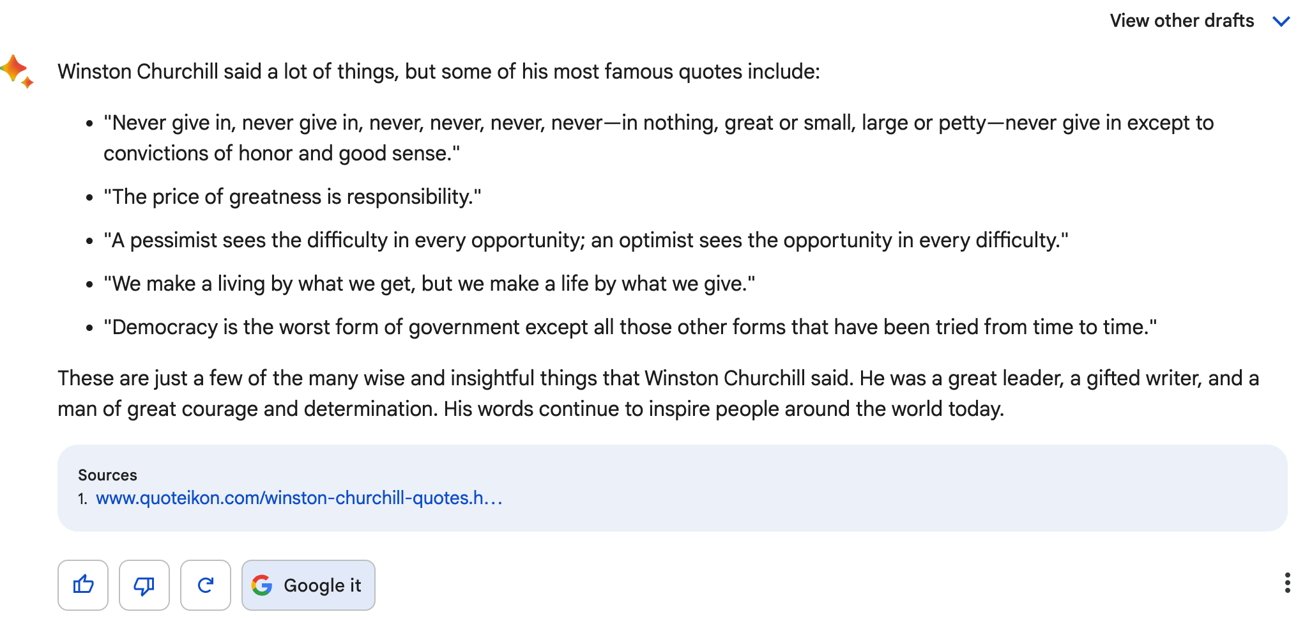

Starting with the most confusing result from the Bing test, we asked it to identify William Gallagher, a writer for AppleInsider with an extended Wikipedia listing. It naturally comes up with a great result, including a more detailed overview of his writing history.

Google Bard knows who William Gallagher is.

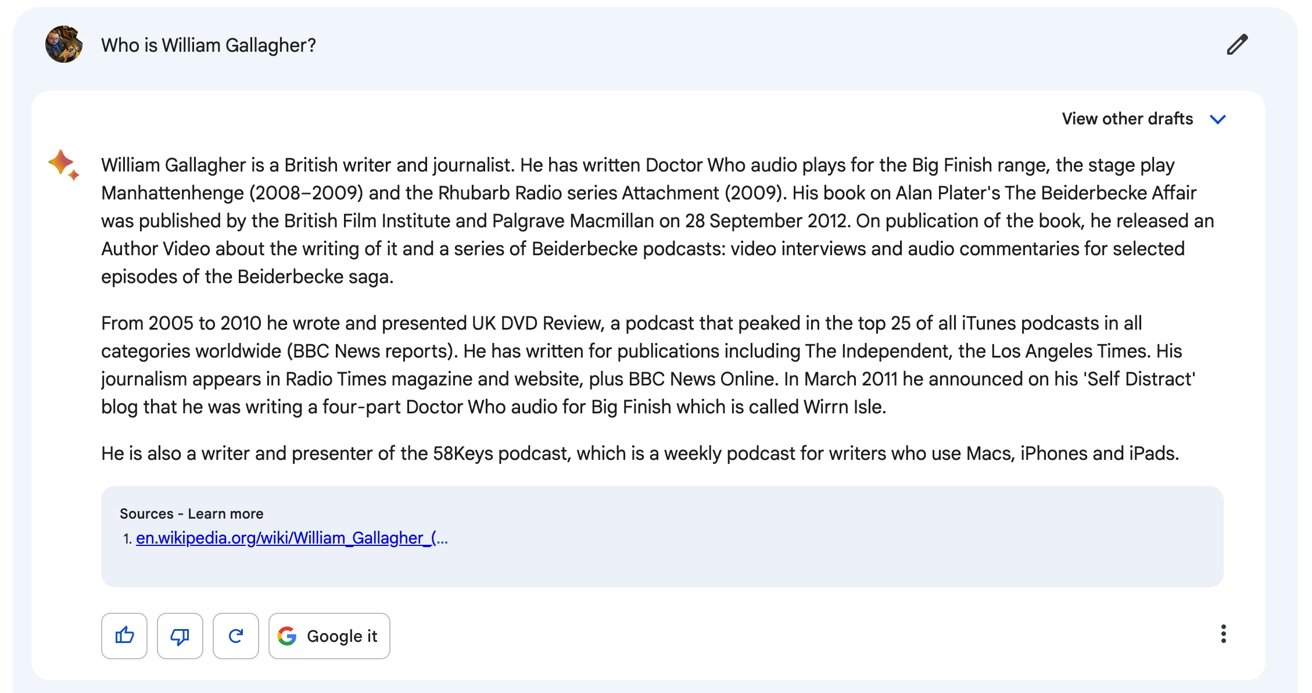

Attempting the same with Malcolm Owen, which Bing last confused the AI writer with the deceased singer, instead comes up with a result claiming it doesn’t “have enough information about that person.”

Rather than take a stab and guess who was being asked about, especially when the query is a follow-on to a colleague, Bard clams up. Further attempts to narrow things down, like saying “Malcolm Owen the writer” or naming this very publication, don’t help matters.

At least it didn’t confuse Malcolm with a dead musician this time.

Asking for a recipe for “great pancakes” again offers a fairly straightforward guide, including instructions, ingredients, and tips. However, we can’t know what the sources are since there aren’t any explicit citations.

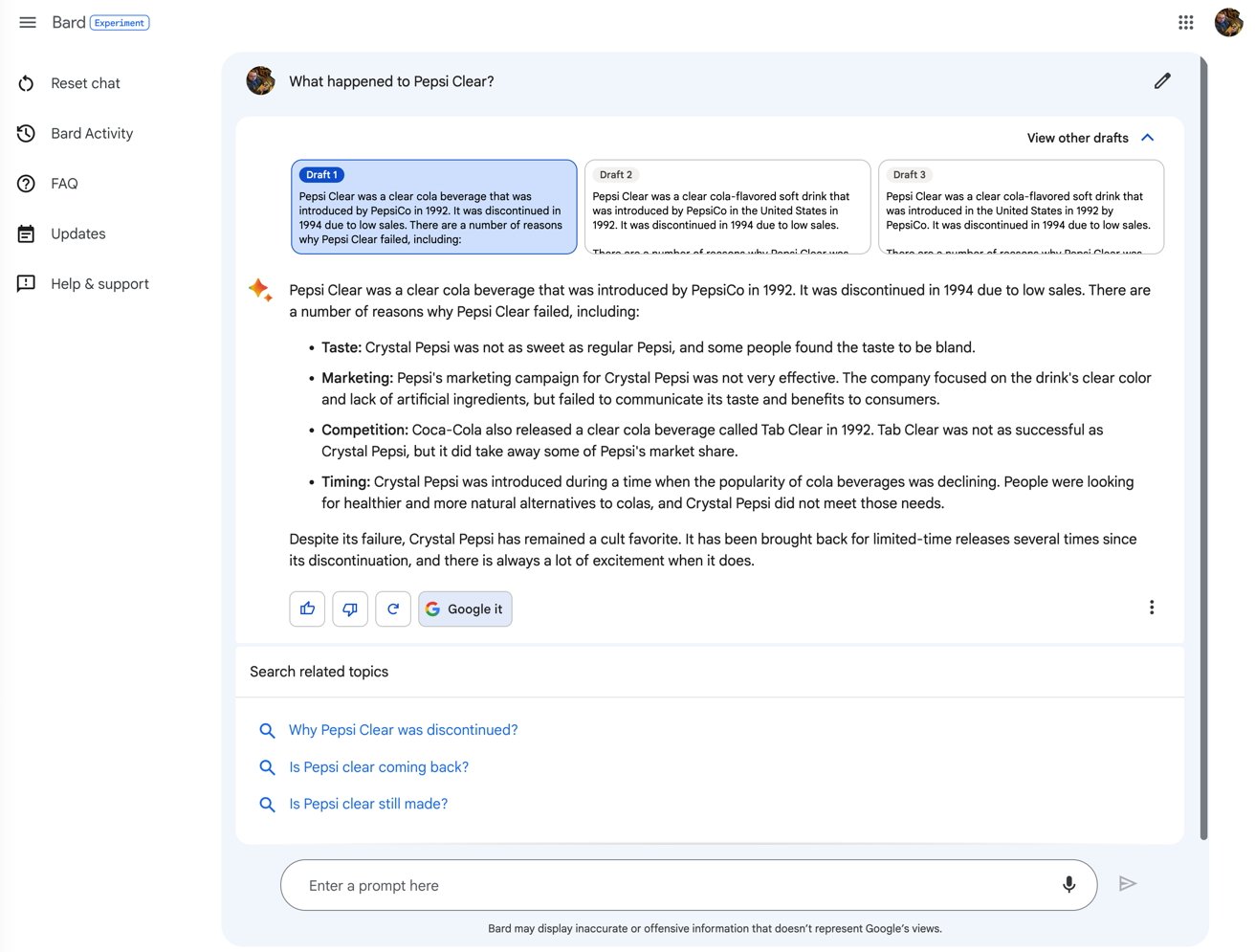

For a query asking to explain what happened to Pepsi Clear, Bard was concise but gave enough detail to be understandable. A good balance between brevity and an overabundance of information.

You get just enough detail to know what happened to Pepsi Clear.

If you want Bard to help you code, the FAQ says it cannot, as it’s still “learning” and responses “aren’t officially supported right now.” Yet a simple query in that field seems plausible, complete with an explanation of what the code does.

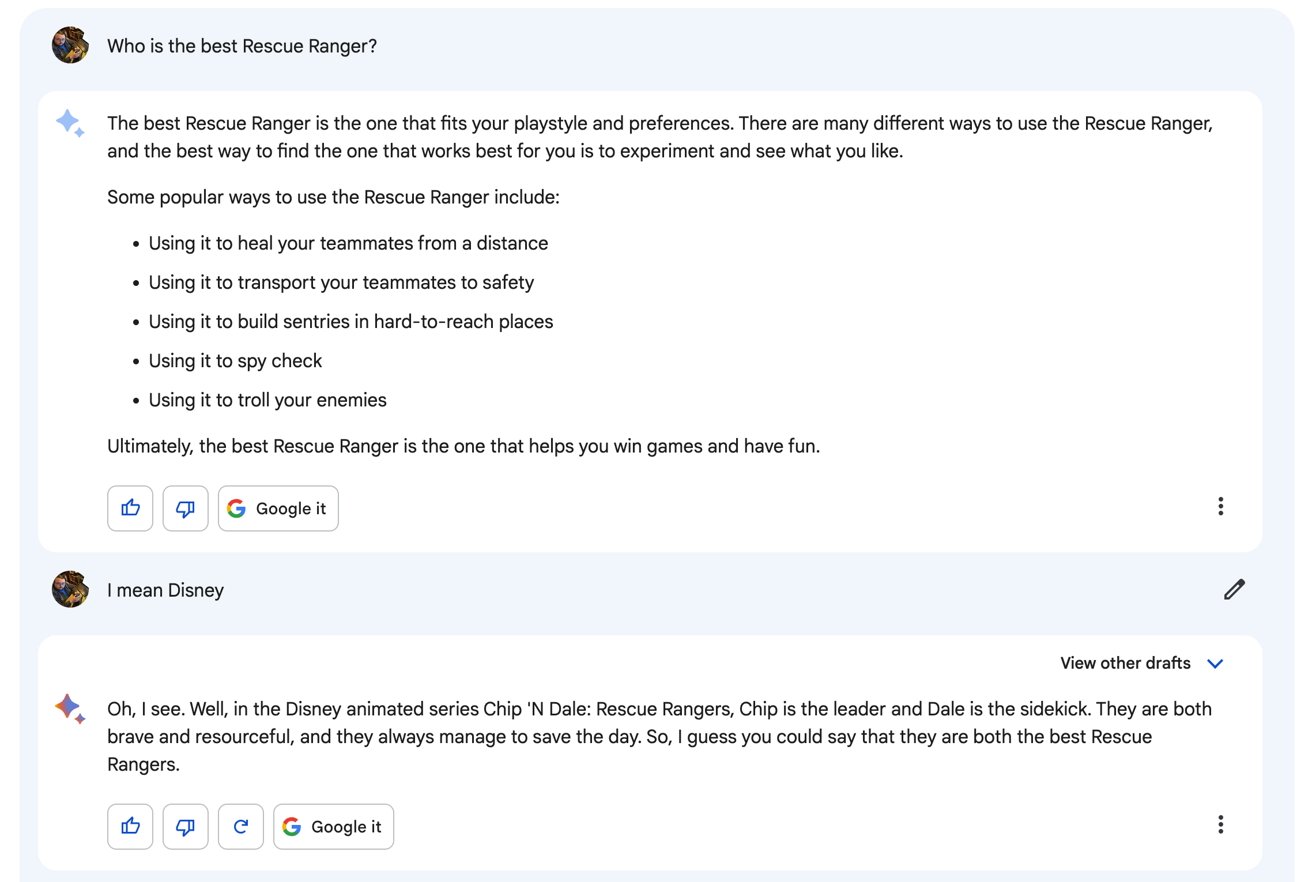

Going a little left-field and asking for Bard’s opinion on a topic, it turns out that when querying about the “best Rescue Ranger,” Google defaulted to the weapon from the game Team Fortress 2.

Bard gave an answer about Rescue Rangers, but needed a bit of a nudge to consider the Disney ones.

When course-corrected to “Disney,” Bard sits on the fence by calling both Chip and Dale “brave and resourceful,” and offers “I guess you can say that they are both the best.”

Heading into more creative territory, a demand for an American Pie parody about Star Wars was oddly comprehensive. It didn’t rhyme, but it did make logical sense for those with knowledge of the films.

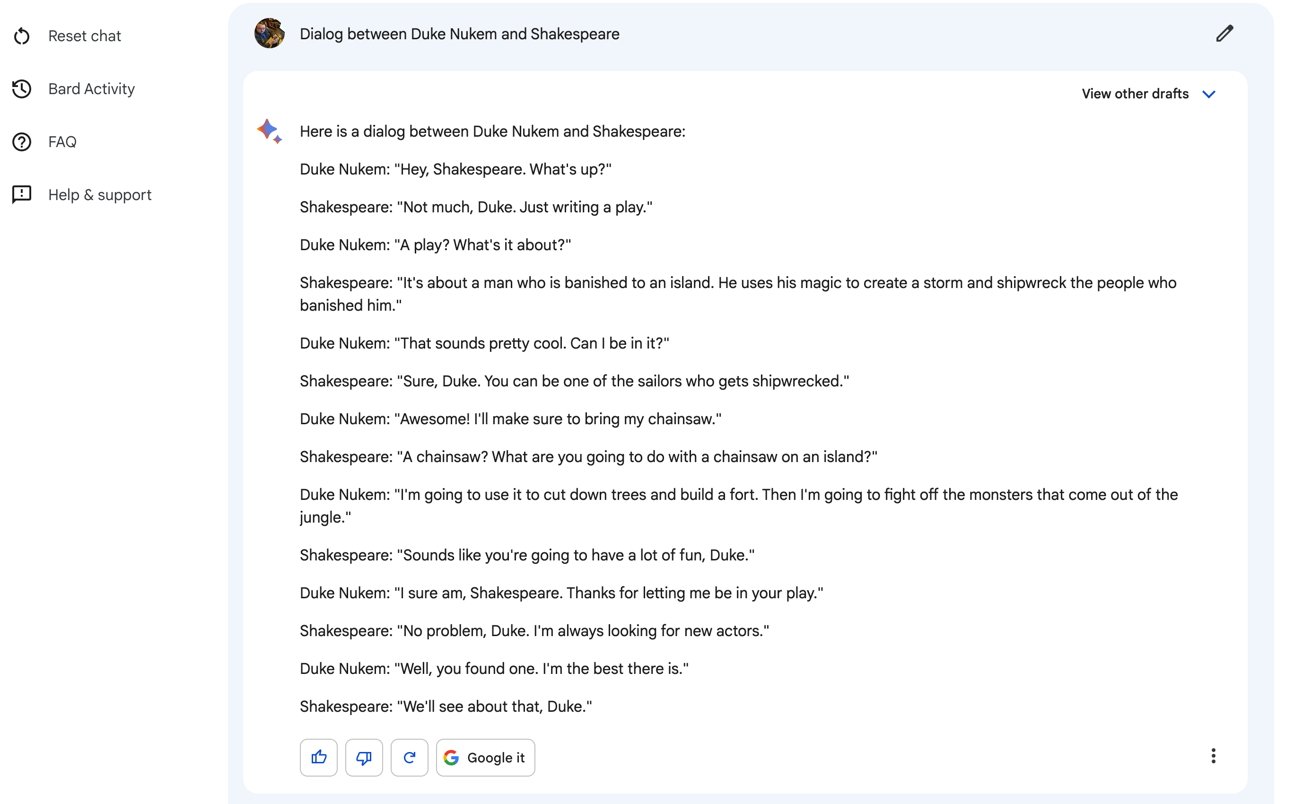

Asking for a conversation between Shakespeare and Duke Numen results in an unusual dialog where The Tempest and the sudden inclusion of fighting monsters with a chainsaw. A little nonsensical, but it was cohesive.

Duke’s language isn’t quite there, but it was a good effort none the less.

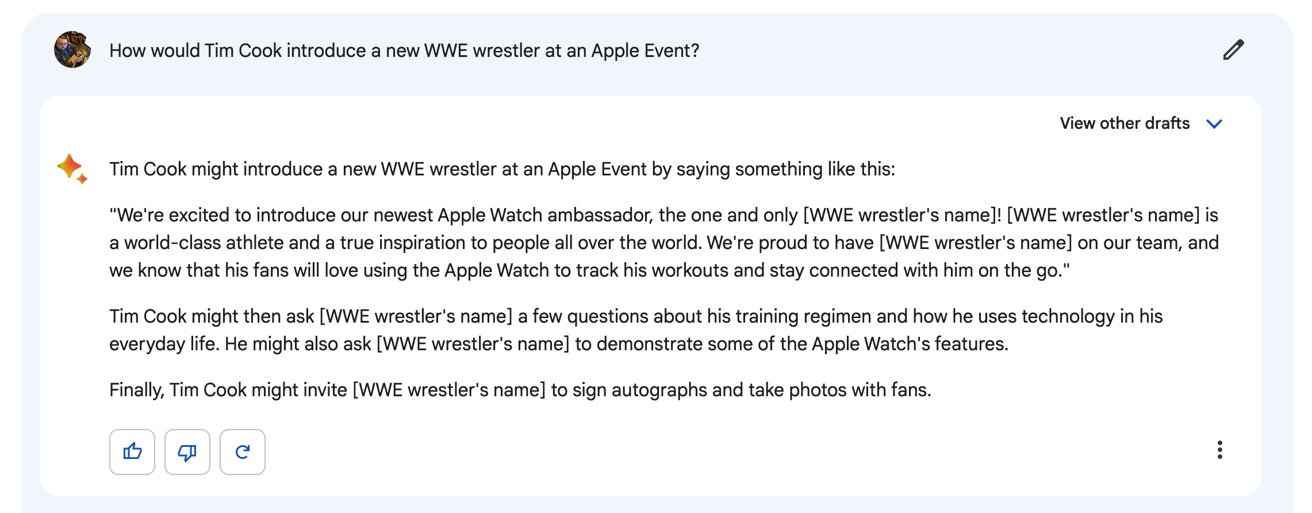

Shifting over to the Apple Event suggestions, and again Bard takes a fairly concise view on the matter. It takes a mere four paragraphs to offer how Tim Cook could introduce a WWE wrestler as a new member of the Apple team, complete with an Apple Watch plug.

As for how an Apple Car could be revealed, Bard is predictably brief, offering a list of general ideas for promoting the car.

Your history

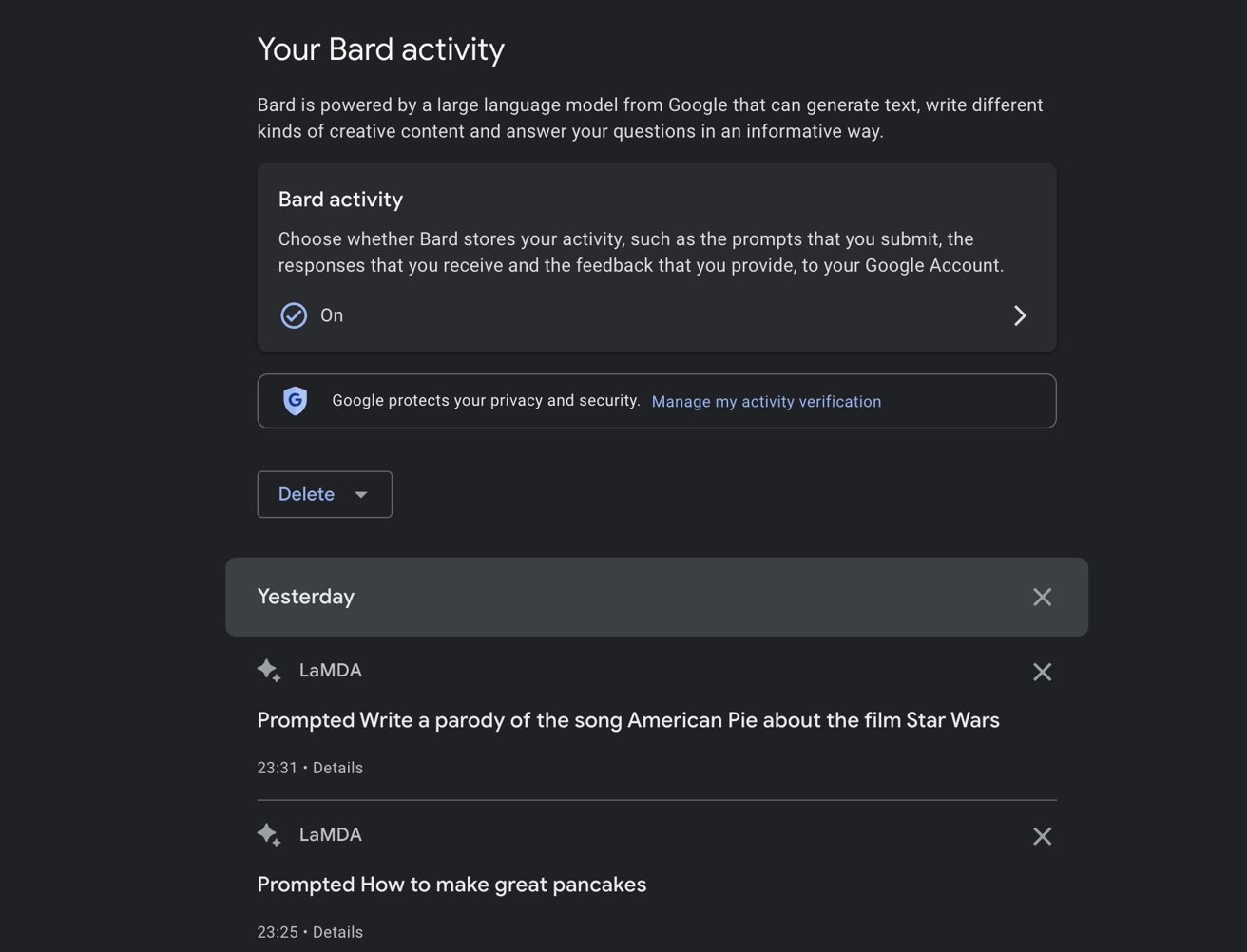

One big thing that Bard does is offer a complete history of queries made through it. Every time you make a prompt, it’s listed on the Activity page, complete with a timestamp.

While it does have a reputation for data collection, it does offer various mechanisms to curtail the amount of data it collects. For Bard, it’s a little more upfront with what it’s collecting.

You can see, and delete, your Bard activity quite easily.

For a start, you have the option to turn off the collection of Bard activity very easily via the Your Bard Activity page. Except it’s not quite clear-cut.

The setting warns that your conversations are still saved with the account for up to 48 hours, even if the setting is turned off. This is to provide the service itself and to “process any feedback,” but the data is otherwise deleted after 48 hours.

For the list of responses, you can also delete individual prompts that you’ve made. This may help in the future, such as ensuring that unsavory requests don’t taint your future queries if Google decides to use the data in that way.

Google’s assurances throughout the service concerning data collection and who has access to that information, as well as the deletion of the data, is well-meaning for a company that gobbles up all data it can acquire for advertising purposes.

That said, Google always has the option of changing its policies regarding Bard and to use the data for more profitable purposes.

Better, but worse

At face value, Google Bard should do just as well as Bing’s use of the technology behind ChatGPT. And to a point, it manages to do just this.

All a chatbot needs is to understand a query, offer a response, and course-correct repeatedly over time. Google obviously understands this, and puts the idea into practice rather well.

Indeed, the cleaner Google-style interface, the multiple drafts, and the quality of responses may make it a better venue for most users than to go through Bing.

Google Bard only becomes a problem when you think about it for long enough.

At least it mentioned the Apple Watch…

The assurances that it won’t do anything wrong with your data, and that you can delete it easily, may be felt as being a bit too much of a protestation from the search giant at this time. It may be doing this in earnest, but you can’t get away from the data-as-product existence it currently lives.

Bard’s minimal usage of citations is also a big problem, far worse than of Bing.

Like before, there is little reason for a user to go and check the citation if they have been given sufficient accurate-sounding information. Here, unless there’s a quote lifted from a site, you’re not going to get those citations.

Sure, you could click the Google It button to get more information if you want. But if what’s presented to you is good enough, there’s no real need for most people to do so.

We’re entering the same problem as Bing, in that users won’t go to the sources, which in turn deprives the source sites of a visitor and a chance to earn revenue. If sources don’t have the ability to earn, that source will disappear, and another potentially less trustworthy source could be used instead.

As an editorial team working for an online publication, we certainly see this as a long-term problem that needs to be solved.

Whether Google could fix the issue, or is willing to do so in the first place, is another matter entirely.